A little house in the ruins of Tokyo

Remembering an old visitor on the 80th anniversary of the firebombing

March 10th marks the 80th anniversary of the Great Tokyo Air Raid, so below I’m re-sharing for new subscribers a story about the “cardboard grandpa” who visited me at Tokyo Little House in 2023. But first, let me explain a bit about where he fits into the history of this place.

It’s now been seven years since my colleagues and I turned their old family home in Akasaka into Tokyo Little House, and six months since we renovated and expanded our cafe and history gallery focused on the postwar ruins and occupation of Tokyo.

Akasaka is not the first neighborhood that comes to mind if asked where to find “Tokyo history.” But a lot of history has happened here, going all the way back to when it was laid out as a compact commercial quarter1 just outside the gates of the new castle in Edo. The closest liquor store to TLH set up shop in 1624. The names of metro stops (“Tameike” / Reservoir) and boulevards (“Sotobori” / Outer Moat) immortalize waterside scenery, long since lost beneath the deluge of concrete, that inspired 19th and 20th century woodblock prints.

Before the war, Akasaka was an army town where officers consorted with geisha. In 1936, fascist insurrectionists stormed out of their barracks (now, of all things, a Harry Potter theater) and raced past where our house stands en route to the Prime Minister’s office and ministries. Their coup failed but war broke out the next year, and in 1945 the area was wiped out by B-29s in a major raid in late May. A carpenter who had been digging air raid shelters built Tokyo Little House in the ruins three years later.

By the 1960s, Akasaka had become Tokyo’s most cosmopolitan district—nightclubs like the New Latin Quarter and Copacabana, once just a few doors down from us, attracted heads of state and legendary international performers. In the other direction, the city’s premier cabaret, the Mikado, employed hundreds of women as dancers, many of whom bathed at the sento next door that my colleagues’ grandmother also went to. The bathhouse and club are long gone, but the surrounding Korean town still has a glitzy bubble-vintage vibe. My favorite 24-hour restaurant across the street has been serving the same Seolleongtang ox tail soup and sides since 1954.

Wander a little bit farther and you’ll bump into the security perimeter around the American Embassy. Over the past few years, Ambassador Rahm Emanuel became a regular at our cafe. He’d stop by for a coffee during the workday with security detail in tow; later he began showing up even more frequently on his own in the evenings, to listen to my colleagues’ daughter practice violin after the cafe closed.

The ambassador’s visits to our cafe were an interesting wrinkle in the history of the neighborhood, particularly now that his ambassadorship seems likely to mark the end of the long era during which America exercised varying degrees of suzerainty over Japan. We made our cafe in part because, while two million people visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum last year, no public museum commemorates the similarly deadly razing of Tokyo.2 Historiographical disagreements and fiscal pressure are cited as reasons behind the Tokyo government’s decision in 1999 to abandon plans for a Hiroshima-like museum, but one has to wonder if a desire to avoid causing discomfort to the Americans may have been another factor. While the first use of atomic weapons can be memorialized as a universal human tragedy and become a totem of the wish for peace and the dangers of technological progress, it is harder to understand the firebombings as anything other than a specific atrocity committed by one group of people upon another. If you want to get a sense of the events of 1945, come to our cafe, order a coffee and pull one of the many volumes off the shelf I built out of old boxes plucked from across the city. Or if you’re visiting Tokyo, stay upstairs.

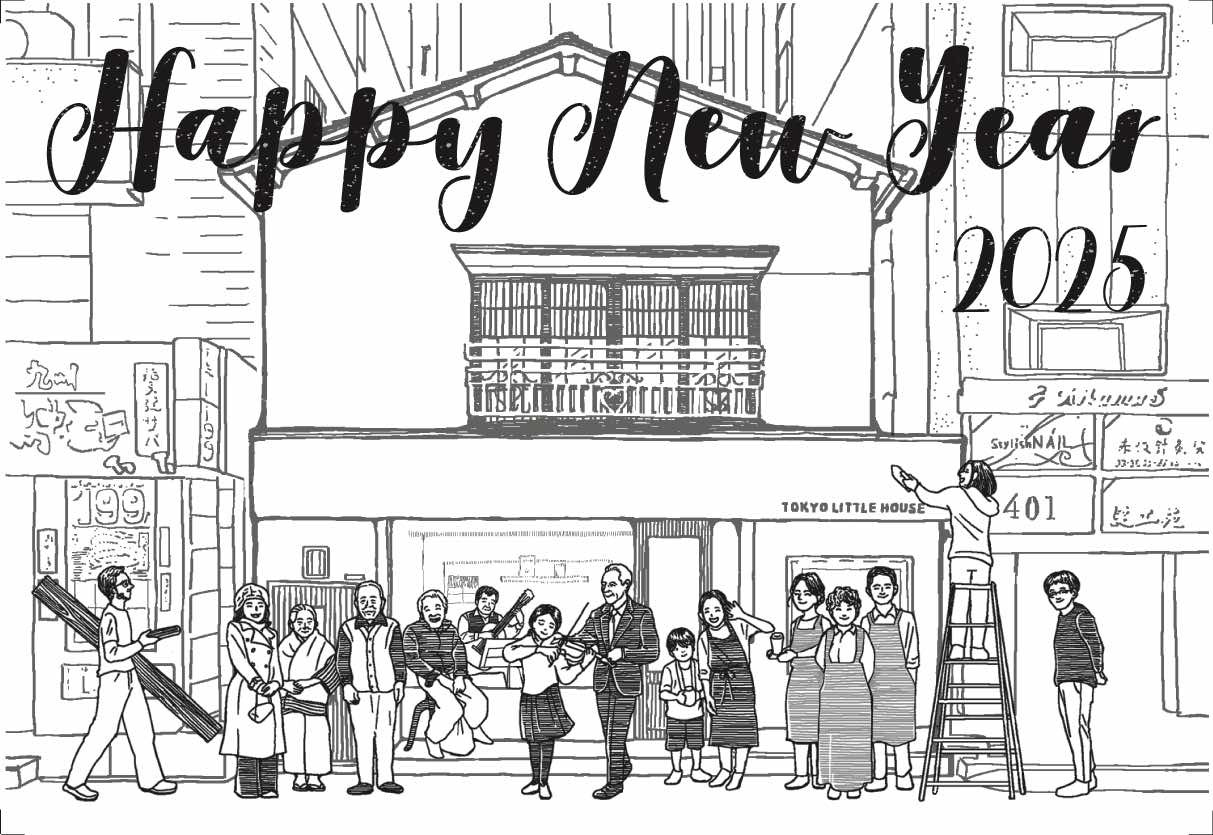

The episode re-posted below was the last time I saw the cardboard grandpa. On our New Year’s card this year, he sits near the ambassador amid past and present faces, part of the story of our Little House that has endured in the heart of Tokyo, from the ruins of American conquest to the twilight of American hegemony.3

The cardboard grandpa

A visitor from another world brings me the most extraordinary gift

“It is also what comes in the wake of war and its fire: a city in ruins, the burnt-out shell of a metropolis. Its creatures have hatched out of the debris, and now they survive by the sheer tenacity with which they came into the world and by which they cling to life.”

—Jun Ishikawa, “The Jesus of the Ruins” (1946)

Marebito (noun): an ancient Japanese word used by folklorist Shinobu Orikuchi; a god who visits from the eternal world across the sea, bringing people gifts of spiritual knowledge and happiness before departing.

Five years ago, we opened Tokyo Little House, a little cafe in a 75-year old house that stands on Tamachi Street in Akasaka. It’s a busy district surrounded on all sides by glass skyscrapers, a stone’s throw from parliament and the prime minister’s office. Each day around noon, our street fills up with gaggles of television producers and expat investment bankers, political operatives and copywriters strolling during their lunch break. If you peek in our window, you’ll see pictures of the fields of ruins that still stretched across Tokyo when Little House was built. We like to think of it as a window open to the past that endures against the odds at the heart of the city.

A few weeks ago, I was sitting at our window counter and chatting with a visitor when I spotted a familiar figure sauntering down the sidewalk across the street. It was the cardboard grandpa, hunched forward with eyes straight ahead, hands clasped behind his back and mouth slightly agape. I hadn’t seen him in two years. Caught up in my conversation, I pointed him out to Ai, who was running the shop and went out to say hello. He stopped and turned, and I watched as his delightful smile spread across his face, and his neck bobbed up and down as he nodded in conversation. Lately my back has been hurting and I don’t get out as much, he told her before continuing on his way. I’ll come back again soon.

When we were renovating the house in the fall of 2017, the cardboard grandpa pushed his cart down the street every few days, always from west to east. The busy world would seem to part at his presence, paying him no mind, yet never blocking his path. Every few buildings, he would stop and fetch another parcel left for him. While can collectors are sometimes seen trundling down Tokyo side streets, cardboard pickers are rarer; a kilo of cardboard will only fetch you around ¥2-5 (2-4 cents) at a recycler.

We began to talk with him, and like others on the street, came to rely on him. We tied up our cardboard and left it in a crack between our house and the building next door, and every few days he would return. We never learned each other’s names. Eventually, he told us he had to take a break from his work for a stay in the hospital. I think he returned for some time after that, but then around the start of the pandemic, he stopped coming to collect cardboard altogether.

Yesterday, I was running the cafe for the first time in a few weeks. We did brisker-than-usual business in the morning, as travelers stopped by after checking out of their hotels, and some Singaporean visitors became enthralled with our collection of old maps. As the post-lunch rush picked up around one p.m., I was tidying up the counter when I saw the cardboard grandpa out the window, this time walking straight toward me and waving. I hurried outside to say hello.

I brought you a fish! His grin widened. Is the young lady here?

He held out a white plastic bag. I untwisted it to find a large, freshly-gutted red snapper inside, its moist red and silver scales glistening. Please grill it in your garden and eat it together! Stunned, I thanked him and asked him to wait while I went inside to put the fish in the fridge and make him some iced tea. He sat down, but a moment later disappeared from view. Returning outside, I found him leaning on the post next to the sidewalk. I don’t want to take your customers’ seats. Not to worry, I told him, and he sat down again and drank his tea. I asked him where he bought such a magnificent fish.

He had gone by bus from his home in Yotsuya to Tsukiji, the neighborhood that was once home to Tokyo’s legendary fish market. Yotsuya is just one metro stop to the west of Akasaka, but in order to get home, he would walk east to take the Shibuya-bound bus to Nishi-Azabu, then transfer to the Shinjuku-bound bus, to make use of his free senior bus pass.

A new group of customers walked into the cafe, pulling me back inside. There was still so much I wanted to ask, but he got up to go, so I asked him if I could take the photo above. I thanked him and bowed as he turned and walked down the street.

The cardboard grandpa once told us about being born in Akihabara, and losing his home at the end of the war. The air raid that erased Akihabara and the eastern half of the city happened on March 10, 1945—78 years ago today. 279 low-flying B-29s swooped over the city at midnight, raining 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs and unleashing a “violent blaze that roared and hurled itself like a flamethrower down the streets, as countless belongings and futons were reduced to so many tumbling embers in a river of fire,” in the words of one photographer who witnessed the hell-scape.4 100,000 people died. My visitor recalled walking through the ruins from Akihabara to Nerima, some 15 kilometers away on the city’s northwestern edge, where he found a place to stay. In 1954, he moved to Yotsuya, where he’s lived ever since. For many years, he worked at a building in front of the American Embassy. That’s how he came to be a part of Akasaka, and ended up staying another twenty years collecting cardboard.

There are moments when people, places or objects that I encounter seem to reveal glimpses of the city’s soul. It’s almost as if that grandpa walked here straight from the ruins, my colleague said when I told him about it. His way of moving through the world more closely resembles the people walking through the photos in our cafe than in the street outside the window. In his time, a fresh fish bought in Tsukiji, grilled on a brazier behind the house, was surely a pleasure of the highest order. Elsewhere in Japan such a gesture would move me, but in Akasaka, in 2023, surrounded by the towers of capitalism indifferent to history, it felt like a miracle.

In the evening, I closed up shop, stopped at the supermarket in the subway station, and stood in the automated checkout lane with other commuters to buy some mirin, sake and soy sauce. I carried the fish home in my backpack, and my skillful partner simmered it until the flesh soaked up the flavor and fell off the bone. We gave thanks to a marebito who had come bearing a gift and left behind a revelation of something more.

We have an original Edo-era map of Akasaka on the shelf at TLH. Please handle carefully.

The privately operated Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, in eastern Tokyo, was established in 2002.

My Tokyo tours, including one on the firebombing, black market, and occupation will resume in the second half of the year. Sorry to those who have been waiting!

Ishikawa Koyo, Complete Record of the Great Tokyo Air Raid

This was a heartfelt and touching read—thank you for sharing. Your very own sliver of what remains of Imperial Tokyo history—and the visit of your marebito—makes the events which occurred in those awful last years of the war, all the more real.

I’ll make sure to pop by and visit Tokyo Little House in the coming months. Looking forward to browsing your collection of books and maps whilst enjoying a coffee. - Cheers

What a great true story about the neighborhood in Tokyo where I had my first full-time job a lifetime ago!