Inari-yu Nagaya in the spotlight & how the quake made Tokyo

Our project is featured in prominent architectural magazine. It's also a product of the Tokyo quake 100 years ago

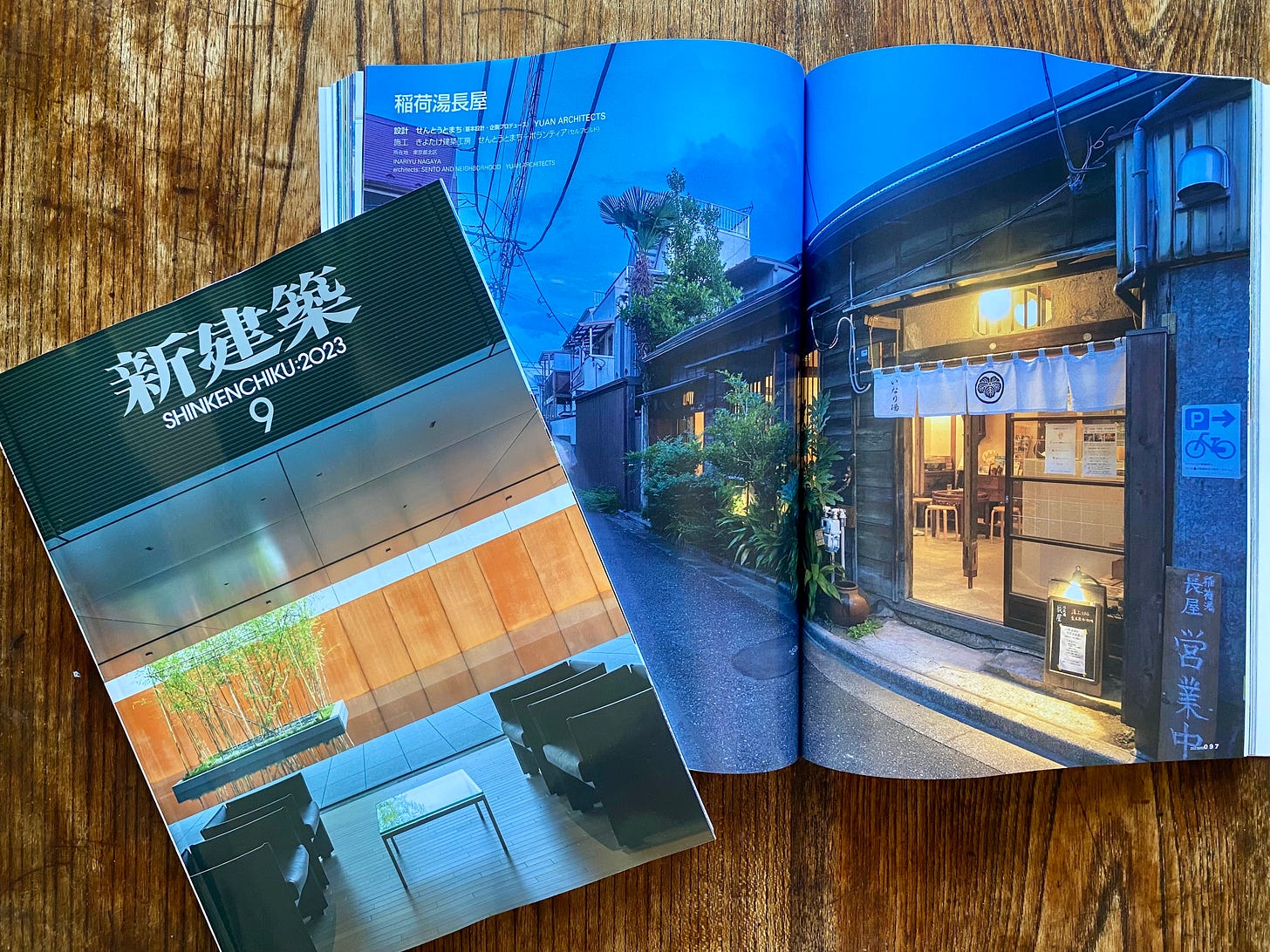

I’m really proud that Inari-yu Nagaya has been featured in the new issue of Shinkenchiku (New Architecture), probably Japan’s most prominent architectural magazine. We’re even the top image on their site this month, which came as a surprise given that, as the name suggests, Shinkenchiku’s pages are usually filled with modern houses by up-and-coming designers or the latest stadia and museums by Japan’s famous starchitects. In that sense, it shows how much the architectural profession is changing in post-growth Japan that our humble little 1920s tenement gets a full spread.

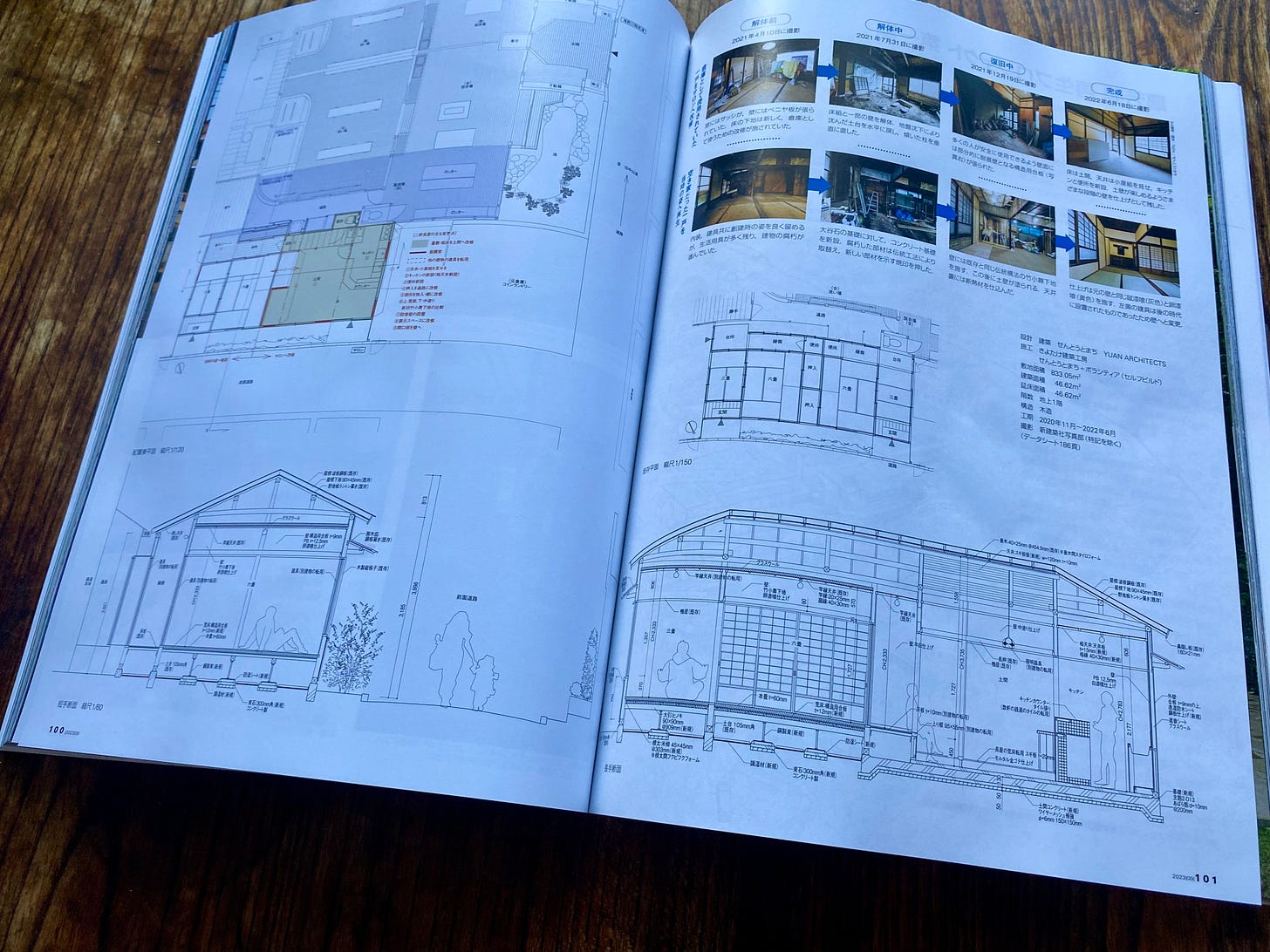

The project would never have been possible without our professional collaborators, especially our carpenters and wall builders. But the editors were partly interested in our unconventional design and construction process, in which we did a lot of the work ourselves. My Sento & Neighborhood colleagues and I are credited for primary architectural design. It’s cool to have my name and picture in an architectural magazine, as there was a moment when I imagined becoming an architect around age 10, when my dad and I were building decks and tiling floors together. Back home in June, I dug through a box in his basement and found an old plan for my dream house—a sprawling American house with a multi-car garage and a silly number of bathrooms (I also recall sketching plans for a book-filled cafe, so I was interested in common spaces back then, too). Soon after, I decided that cars were the source of all our problems and that I should be an urban planner instead, which was before I went to Japan at 16 and realized that I’m probably better at the whole culture thing than engineering. In the end I found my way to urban sociology via IR, history, and geography.

And yet I’ve been lucky that desire comes full circle, and in my late 20s and early 30s I find myself living an amateur architect/carpenter’s dream. I’m currently working on my fourth & fifth renovations, after creating a cafe in Tokyo, a house in Onomichi, and our community space at Inari-yu Nagaya. Doesn’t earn me any money, but maybe it’s better that way. It keeps the co-creative process feeling like play. More than a year after completing Inari-yu Nagaya, I’m eternally thankful that we got the big questions right (at my lowest point, accumulated stress and agony over deciding one important change landed me briefly in a mental clinic). The little mistakes, the millimeters and details that long kept me awake at night, have slowly receded in the mind. The important thing is that it’s done and awesome, and it feels great to know other people think it is too.

The quake that created Tokyo

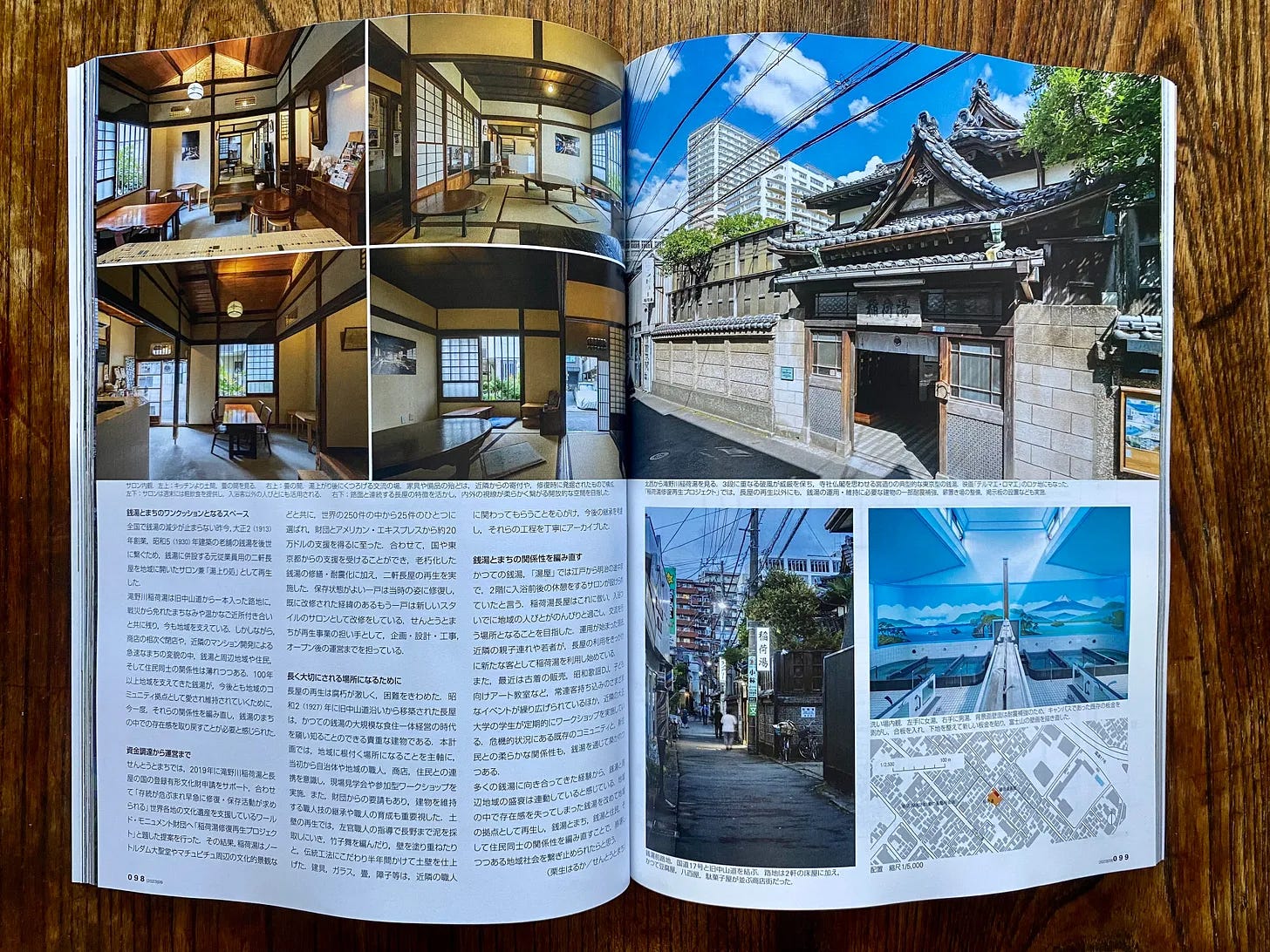

Incidentally, the day Shinkenchiku went on sale on September 1 was also the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake, which played a key role in the history of Inari-yu and its neighborhood of Takinogawa. All the retrospectives last Friday understandably focused on the physical destruction of half the city and the terrible death of 100,000 people. The basic narrative of Tokyo has always been of a cycle of repeated destruction, followed by modernizing phases of reconstruction. This is certainly true, but the reconstruction phase of this narrative usually focuses on top-down modernization of the urban core, and most stories don’t bother to talk about the very rapid urbanization on the periphery as refugees were displaced. How the earthquake tipped gradual change in places like Takinogawa into full-blown urbanization almost overnight, bringing about all the bathhouses and small shops and other pieces of local neighborhoods.

In 1923, Takinogawa was a gradually urbanizing town on the outskirts of the city and avoided major damage from the earthquake. One account I found when researching local history this spring recalled refugees from the burned-out center city flowing down the Nakasendo Road day and night for more than a week after the disaster. The closest elementary school nearly doubled in size between 1922 and 1928. A woman who worked at the school recalled that “the days began and ended with the sound of hammers.” Within ten years the area was fully urbanized and incorporated into the municipal boundaries. In the rush of construction, our nagaya was taken apart in 1927 and sold to the nearby bathhouse, so our project is also a direct product of the earthquake.

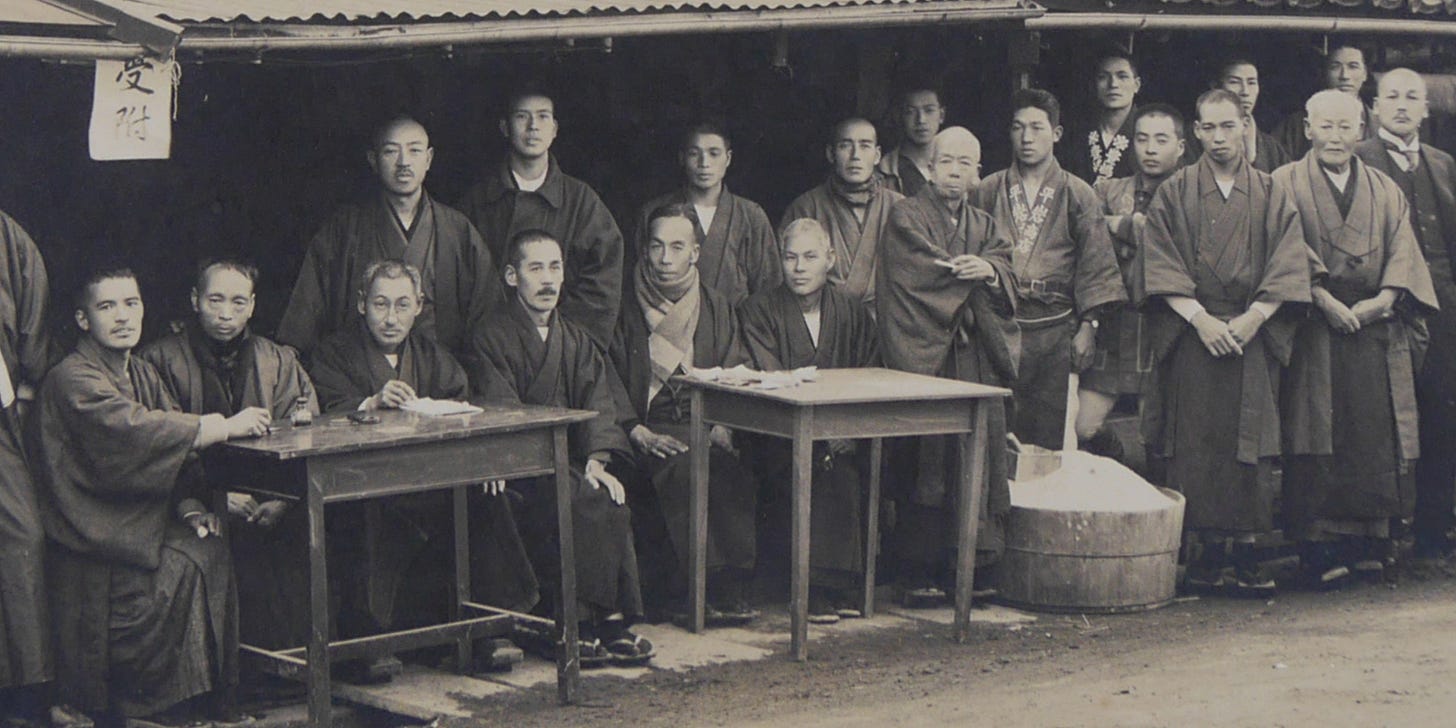

The most remarkable photograph to emerge from our community workshops so far was taken a few months after the earthquake, on the Nakasendo just around the corner from the bath. The sign on the left reads “Rice will be distributed to those recognized as disaster victims as of November 15.” The curator at the museum who helped me digitize the photo said people got two cups a day in Takinogawa. Not bad!

I love looking at these guys’ faces. The neighborhood staring at us through time, eyes I never would have seen if we hadn’t built the Nagaya. That makes me feel strangely connected to them, indebted to them.

Ironically, a century later the districts like Takinogawa that emerged in the aftermath of the earthquake are now among the city’s oldest and most vulnerable to firestorms when the next earthquake inevitably hits. The city administration is now systematically seeking to remake these neighborhoods by rebuilding fireproof structures and widening roads through webs of alleys (read Shoko’s story here), a process they claim will take until the 2040s and that serves to make the Nagaya and the tight-knit neighborhood around Inari-yu ever more invaluable. Many of the surrounding alleyways won’t be around for much longer.

If you’re in Tokyo, you can also drop by my other space at Tokyo Little House, where we have put a lot of our original documents related to the disaster, its aftermath, and the city’s subsequent reconstruction on the shelf in our cafe (more news to come about Tokyo Little House in the near future).

Lastly, in December I wrote about being the last person to bathe at an old sento closing down in eastern Tokyo. A few weeks ago I returned before its demolition to record the space with my colleague. There’s a particular feeling to a shuttered bathhouse—not just the aura of abandoned architecture. It’s like being in a moment outside time where the (usually unseen) intimate spaces of labor behind the wall converge with the (now vanished) social meaning of city’s most foundational commons. You can see some photos of that bathhouse in this month’s newsletter for my org, Sento & Neighborhood below, as well a list of as more than a dozen other bathhouses we’ve documented on our website. That’s all this time.