More on Tokyo demographics & the spiky bucket

How will the post-growth future arrive in Tokyo?

I was glad to hear from good number of people who found my spiky bucket model of post-growth Tokyo insightful (read my last post first). A bit more on that below, but in case you’re wondering, this blog will not always be about wonky stuff like this. If you signed up for the renovation stories or bathhouse philosophy or portraits of the people I meet in my work, there will be more of that in the future. Now that I have the time to write more often, there will also be some urban criticism, theoretical reflections, fruits of amateur historical research, and thoughts about my life and how I got here.

Tokyo’s demographic outlook

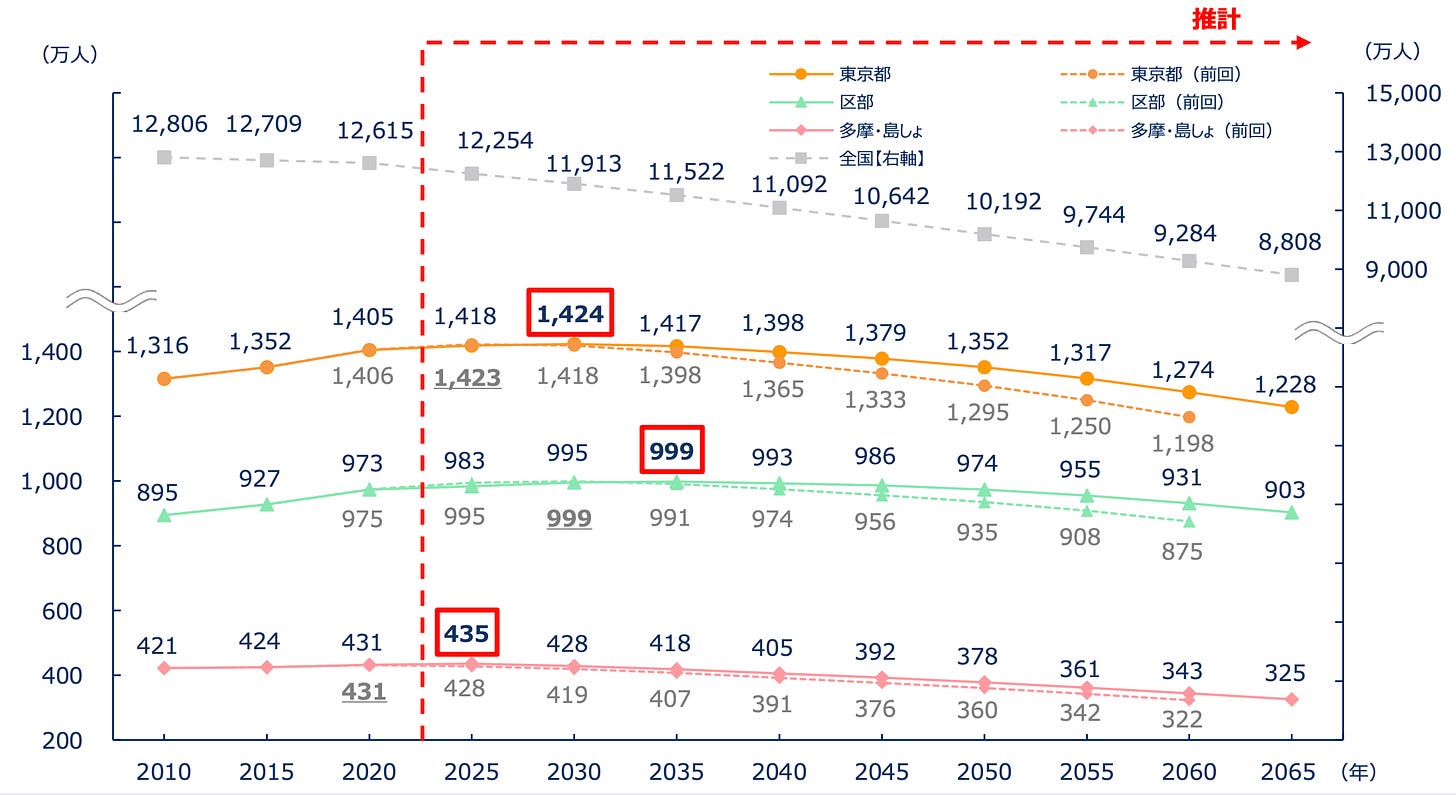

My spiky bucket model was deliberately abstract, so some readers might have wondered, how and when is Tokyo actually going to shrink? Last week I found the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s latest demographic projections from its January update to its urban strategy. It’s a nice document to peruse if you’re interested in this topic. The TMG currently projects the population of Tokyo (orange line) will peak in 2030, five years later than its previous projection in 2021. The 23 wards (green line) will add a few more tens of thousands of residents before beginning to decline after 2035.1

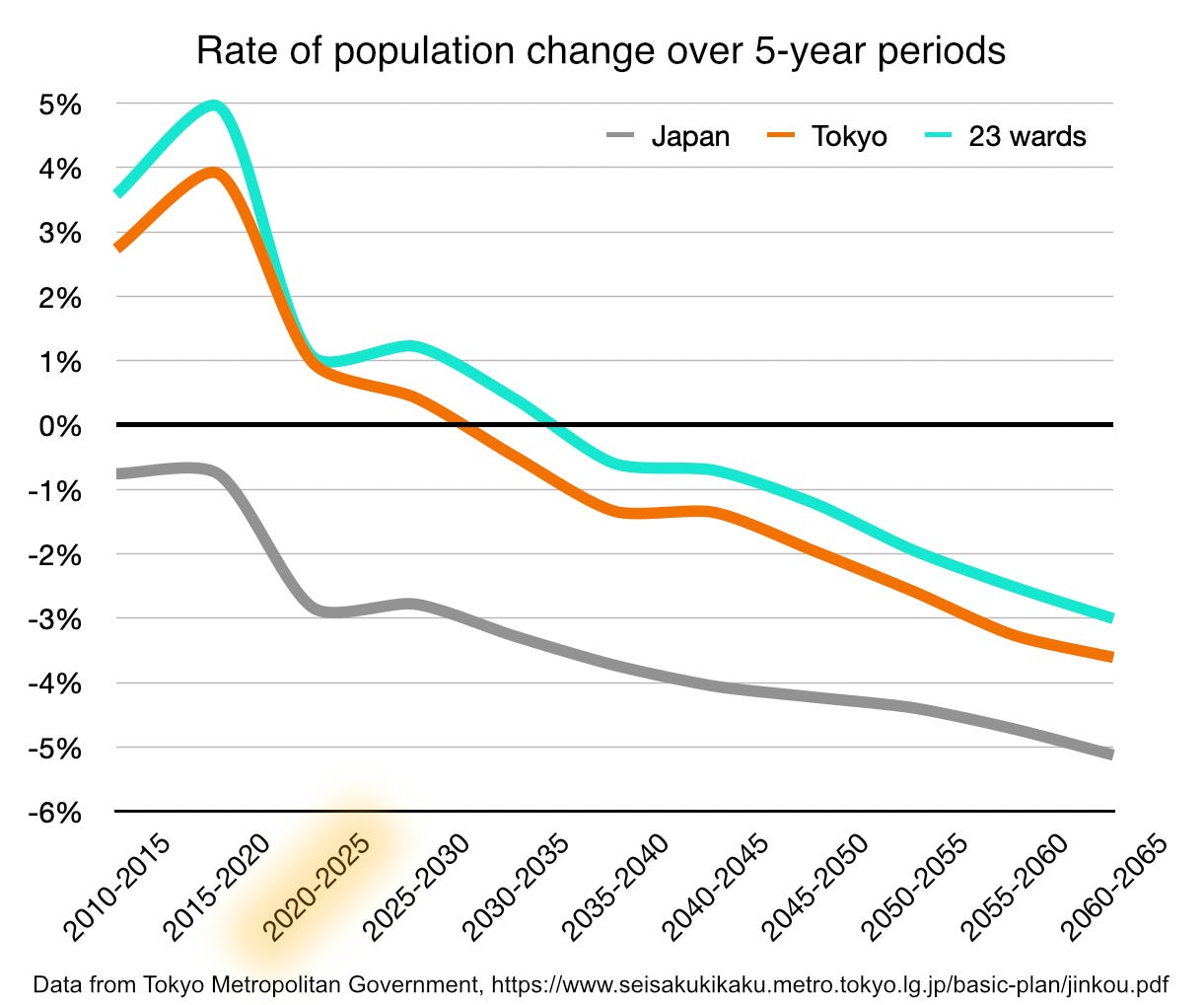

I made the following table of the rate of population change during each five-year period in the above data. Take a look at where we are right now:

After Tokyo pulled Japan through the growth era, population decline is now closing in from the rest of the country. The graph above also reinforces my argument that the Tokyo Olympics/pandemic mark the end of a transitionary quarter-century chapter between the burst of the bubble and the onset of demographic decline. Although Japan’s population began declining in 2010, it was declining very slowly. Now we are entering a much more rapid phase. And while Tokyo was still growing robustly until the pandemic, it will peak in the 2020s and enter decline in the 2030s.

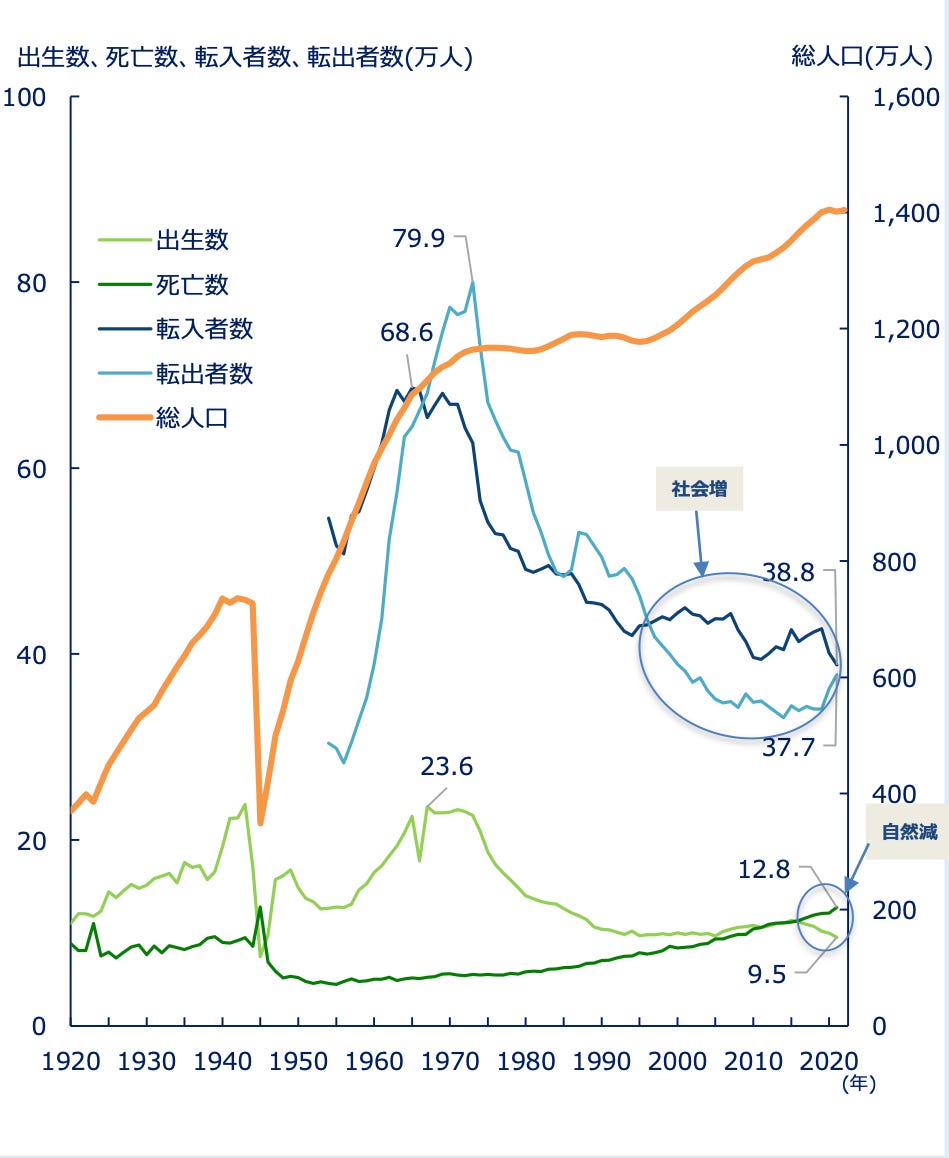

Two more graphs before I talk more about my spiky bucket model. The first separates the components of demographic change. The rebound of Tokyo’s population (orange) post-1995 can be explained by the divergence of the light blue (departures) and dark blue (arrivals) lines (i.e. social increase). The post-2020s decline will be driven mostly by the divergence of the green lines indicating births and mortality (i.e. natural decline).

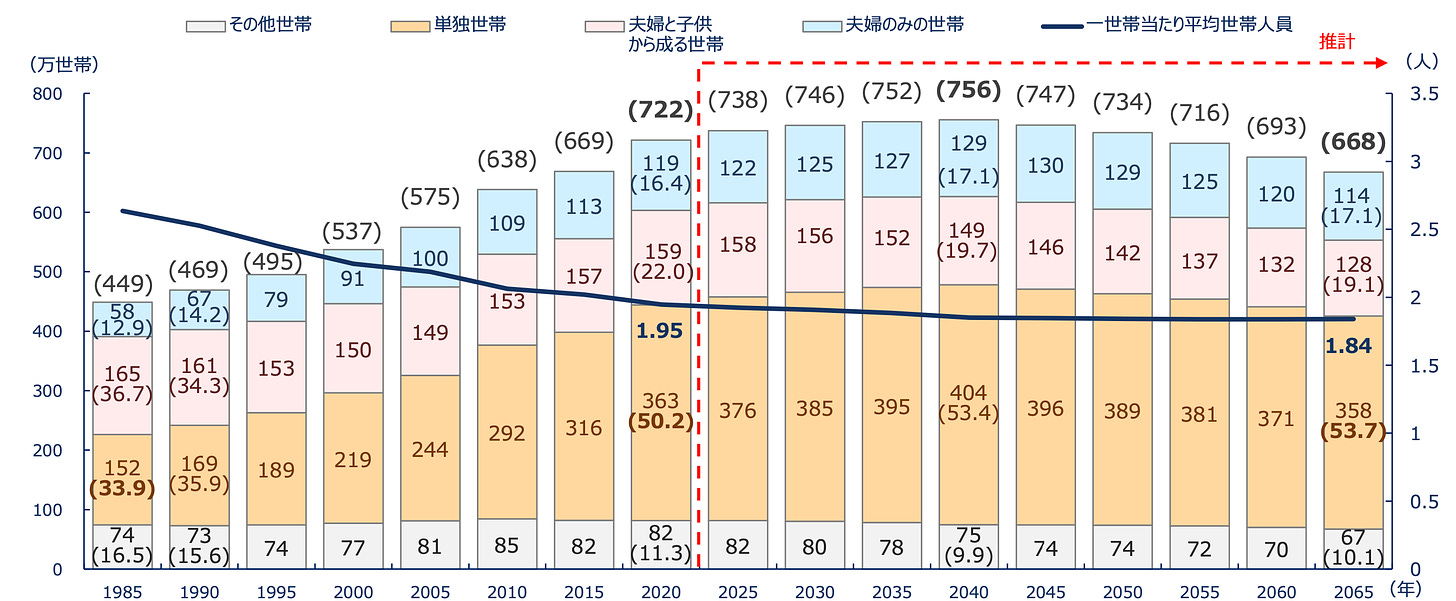

Lastly, a part of the answer to “why are we still building so much?” is that decline of households lags overall population because more people are living in 1- or 2- person households. The TMG currently projects that households will peak around 7.56 million in 2040. That’s about 340,000 more households than 2020, but small compared to the 1.85 million households added between 2000-2020.

So why a spiky bucket?

Regardless of whether Tokyo’s population enters sustained decline in a few years or a decade from now, the spiky bucket model seemed useful to illustrate some things about the post-growth city that are not immediately obvious. There were a few shortcomings with a more obvious topside-up spike model. First, simply imagining urban intensity growing skyward suggests that potential growth is infinite. But to believe that infinite economic or physical growth is possible amid Tokyo’s expected population decline requires us to believe in ever-accelerating increases in productivity, as well as accept a city rebuilt around consumption and production in ever-greater quantity.2 By flipping this open-ended model upside down, we can introduce concepts of capacity, inflows, and outflows.

Second, how does new development impact the overall system? In a topside-up model, we might imagine that developers exploit big differentials between present conditions and developable intensity, push spikes upward to capture profit, and a certain amount of the energy added by new intensity trickles down to adjacent areas in the form of higher values, population growth, and increased convenience. A water-in-bucket model reverses the role of gravity to demonstrate how development sucks energy from its surroundings in a post-growth context. Consider Japan as a whole with the spiky-bucket model: Tokyo already sucks much of its vitality from elsewhere in the country.3 Geographers here have long discussed the “straw effect” (ストロー現象)that occurs after bullet trains or other high-speed transport connects major cities to smaller areas. Wrapped up in growth rhetoric, these investments are typically heralded as delivering Tokyo-like modernity to the periphery; in practice, they often funnel people and industry into the black hole-like center.

More generally, a shrinking urban population is often associated with a particular kind of post-industrial decline and suburbanization, but there will be no concentrated, synchronous hollowing-out of post-growth Tokyo. The idea of dry patches in the bucket model is a way to express how the impacts of the end of growth seep into the city’s margins; I also like the concept of “urban spongification” that’s sometimes used in Japanese (都市のスポンジ化), which asks us to imagine holes or pockets of air opening at random across the post-growth city.

Air pockets are what I look for as an activist wanting to reclaim vacant spaces for a new urban commons. But not all devalued real estate is created equal: an air pocket in a vacant storefront on an old shopping street can be turned into a commons simply by rolling up the shutter. Empty rooms in high-rise apartment blocks or office buildings, or modern houses that shut out the city, are less adaptable. This is why I worry about a hangover from overdevelopment: we are losing many of the city’s most porous, adaptable spaces; the ones most tied to its historical urban rhythms; the places that could be the building blocks for a post-growth urbanism in the future. As the city is rebuilt into more enclosed, segmented, and commercialized architecture, we lock ourselves into a future of social atomization and everyday life mediated by the market.

A few critiques

I made the bucket model as a fun thought experiment, so of course it is reductive. A family member questioned a few of the premises of my argument from a U.S. perspective.

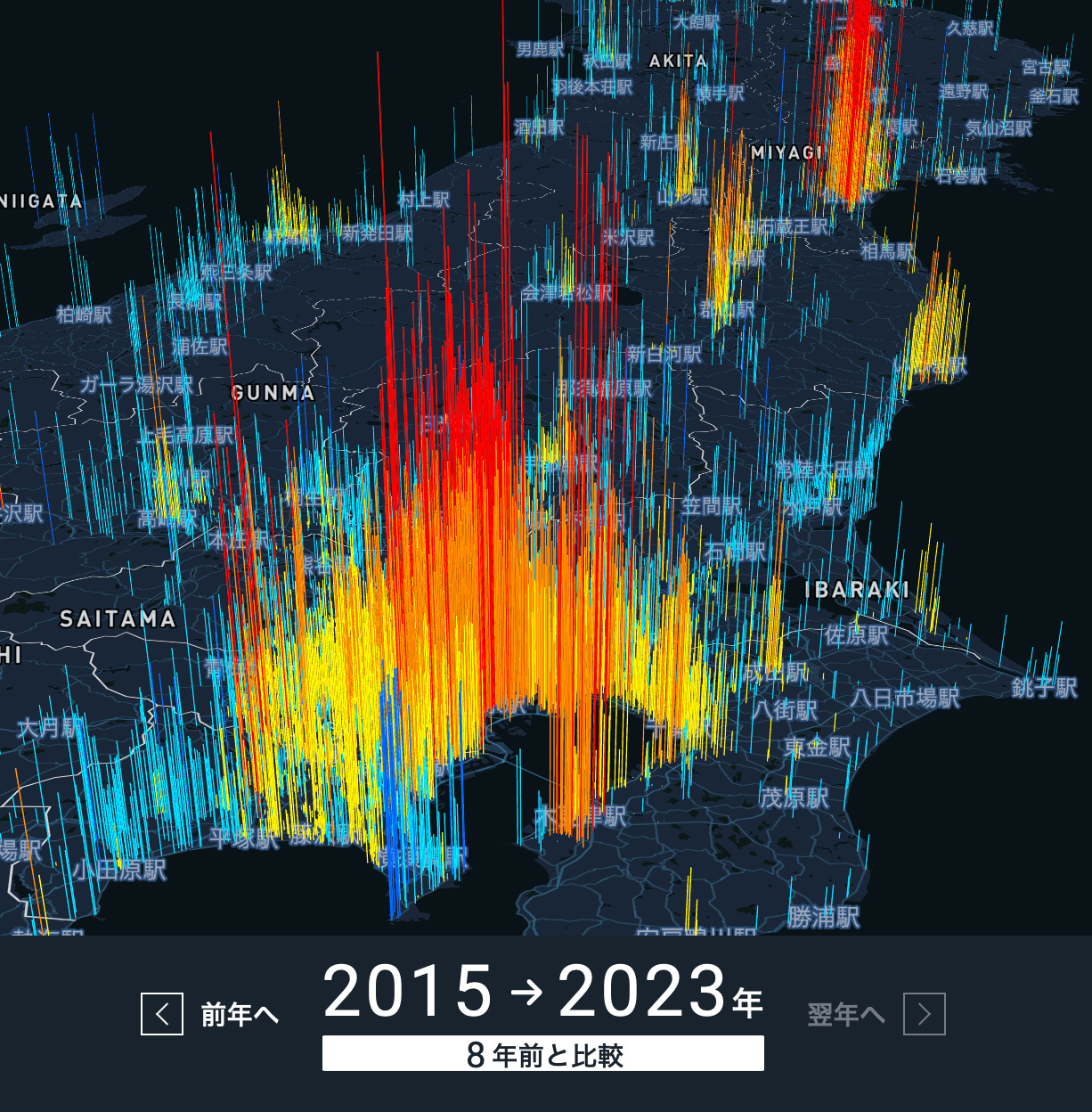

Looking at this graph of real estate price growth from the last post, if Tokyo didn’t build so much, wouldn’t the rise in prices have been much higher and made it more unaffordable for the people who want to live there?

It is true that real estate prices are up across the city significantly in the last decade. Of course this is partly demographic-driven supply & demand, but it seems to me that the current real estate bubble has a lot to do with the very cheap price of money, both for developers and mortgage borrowers, and changes in recent decades to the land-use regulatory regime connected to the government’s growth strategy. So I don’t think it’s right to assume that spiking real estate values signals a shortage of supply, as in American cities, or that the solution should be to build more.

For example, some of the highest appreciation between 2015-2020 was in the area around Asakusa, home to the famous temple at Sensoji. This is not because of a sudden surge in Tokyoites desiring to live in Asakusa—it’s mostly due to the development of hotels and new businesses catering to inbound tourists, which is a key growth industry. In addition to relaxed zoning regulations, office developers often get huge public support for mega-developments by including disaster resilience features or other things in their buildings. Now, we could debate whether said growth strategies are necessary to keep society from collapsing, but I would hazard that the pressure of social increase of population is now a relatively small contributor to real estate appreciation in the city as a whole.

But wait, aren’t you basically just being a NIMBY?

Recently anti-NIMBY (aka YIMBY) arguments have been embraced by many liberal Americans of the sort who read Ezra Klein, Derek Thompson, and Noah Smith (oh hey, that’s me). This is great, as I mostly agree with their “supply-side progressive” critique of why American cities are dysfunctional and unlivable. Suffocated by exclusionary zoning and sadly suspicious of transit, these cities could and should learn many lessons from Tokyo’s default acceptance of building and change over the past 75 years.

Hah, easy for you to say, “build in Denver! But not in Tokyo!” Sounds like classic NIMBY rhetoric. Well, I’m making an argument about how Tokyo should think about itself going forward, not what it should have done as it grew over the past 75 years. YIMBYism isn’t a universal virtue; it’s highly contextual to its time and place. And I’m arguing that the important thing to understand about Tokyo’s time and place right now is that it is becoming a post-growth megacity.

U.S. cities need a lot more urban intensity almost everywhere in order to increase their livability and reap the benefits of density. Tokyo and other Japanese cities going forward need to preserve their human scale and ensure that communities can thrive and continue to produce culture as population declines. Different urbanisms are needed.

Keep in mind that there are three geographic scales mentioned in the previous post and below. From smallest to largest with 2020 populations:

The 23 wards (9.733 million): Tokyo’s core districts, about the size of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens

Tokyo (13.982 million): political unit made up of the 23 wards and western suburbs

The metropolitan area (37.832 million): urban area home to 1/3 of Japan’s population

Consider the city through the standard economics premise that growth is labor + capital + productivity. If demographic decline shrinks your population, and the built environment is already saturated by capital, the only choice to maintain growth is to boost productivity at an accelerating rate. New capital investment must destroy the existing built environment in order to reshape urban life into more productive circuits of production and consumption (“the annihilation of space by time” per Marx by way of David Harvey). The implication is the constant, ever-more invasive transformation of everyday life, which is precisely what techno-utopians, AI accelerationists and smart city evangelists wish to do. Such thinking leads to growth advocates like Shinzo Abe arguing that Japan’s depopulation is not a crisis but a bonus that will inspire greater strides in productivity, while never stopping to consider what ever-accelerating productivity implies for the texture of everyday life, human relations, or the spaces we occupy. In this vision of urban life, there is no room for the unhurried fishmonger, the ambler, or the un-commodified idle moment; everything must make way for robots and algorithms, for spaces and ways of life that are fully optimized for capital accumulation. Does that sound like a richer city to live in? But I digress, this is a topic for another post.

Of course there urban→periphery trickle-down effects at play as well, like the tourist boom in Kanazawa after the Hokuriku Shinkansen, but such developments can no longer serve as the basis for sustained growth of the whole system.

Really enjoyed this. Thank you.