After two weeks away from Tokyo, I was devastated to see this down the street from Inari-yu on Saturday:

Yes, this is Tokyo and the city is always changing. Rarely does a month go by in Takinogawa without some of the little houses and narrow alleyways that contribute to the neighborhood’s urban landscape getting replaced by plastic boxes with carports built by Hebel House and Panasonic. But please, why, not this one!

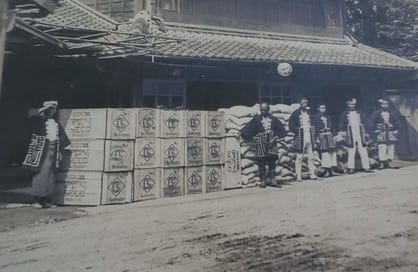

Let me explain briefly: Takinogawa sits along the old Nakasendo Road to Kyoto. It was once a small farming village outside Edo that flourished selling seeds to travelers, and over the centuries, the highway became lined by dozens of seed sellers. One of the three big ones was Masuya, which was established at the end of the 17th century around 100 meters away from Inari-yu. Masuya had been rebuilt around the 1890s. Here’s an image of the shop around the 1910s, with a shipment of seeds bound for San Francisco:

Last year I was doing research at the local library and asked the librarian if he knew when Masuya was knocked down. What do you mean? he said. It’s still there! When the business stopped operating in the 1950s, the family didn’t want to the street to appear abandoned so they put the building on rollers and pushed it 15 meters back on their big plot of land, and built a few buildings in front. It turns out I had been walking past it for years and never knew! Sure enough, I peeked through a gate and down the driveway behind a white Audi, the big old house sat untouched.

Sometimes I like to imagine the things I would do if some patron gave me ten million dollars to intervene in the city. Omnipotent Sam was going to buy this house, tear down the buildings in front and create a little pocket park with benches around a big weeping cherry tree that you could see from the first-floor veranda. I would operate it as a teahouse like the ones that used to serve Edo-era travelers.

Contacting the owners had been around #25 on my list of things to do this year. I figured that if they had kept it intact since the Meiji era, I didn’t need to rush, but such complacency is never a good idea in Tokyo. At the very least, we would have documented it and I could have rescued its fittings and wood for future renovation projects. Now its potential as an urban commons, even if just a figment of my imagination, is foreclosed forever.

I went talk to the old lady who lives on the corner. They’re selling it off to pay the inheritance tax. It’s always the inheritance tax that gets them.

These days Tokyo has become a proxy fight in the Western YIMBY-NIMBY war on Twitter, where some lament the constant destruction of the past, and the other side often responds with a let-all-of-Tokyo-be-smothered-in-shopping-malls shrug.

If you’re on Team Change, you know that regeneration is essential to keep the city economically vibrant and housing affordable, and nostalgia for the past is a brain-rotting virus that leads cities down the path of physical stasis and social self-destruction. Start down the slippery slope of preserving the status quo, and before you know it, Tokyo’s just another Long Island suburb full of reactionaries suing the neighbors for painting their garage yellow.

Sure, I get it, but reality is never as black and white as internet culture demands us to present it. Urban change is good, but the past does matter. Cities have souls, and I’m pretty sure one can’t be found in the Nike Store in Harajuku. It’s not impossible to hold these opposing ideas in mind at the same time. Craig Mod, connoisseur of the disappearing beauty of Japan’s Showa-era kissa, has written about the tension between the benefits of urban churn and the constant sense of loss during his multi-day walks across the city. Here’s a tidbit from his TOKIO TŌKYŌ TOKYO newsletter in 2022:

Tokyo wealth is capped, practical, within the bounds of reason. Old estates disappear because the inheritance tax is so aggressive. One of many tools that's helped flatten Tokyo society as we experience it today […] That tiny plot of old apartments would have cost the children of the owner millions to keep — just to pay the tax. And so it's sold to a developer. For considerably profit, yes, but also with a huge chunk of that wealth weaving its way back into the greater social fabric.

In the big picture, I’m basically where Craig is on this one. It’s actually quite remarkable how simple tax rules can shape vastly different social realities over the course of decades. You can imagine that if the inheritance laws of the United States prevailed in Tokyo, the three big landholding families in Takinogawa would still be living on sprawling estates. Maybe I’d be priced out of the city and raging against the boomers from an overpriced apartment on the fringes of Saitama. Instead, the great equalizer of estate taxes and subdivision has whittled their land down to such small size that it’s not much different than many of the surrounding plots!

Even though this system may work overall, ideally you want some exceptions. Obviously, people would be freaking out if shrines and temples were getting knocked down for homogenous development. But shrines and temples are tax exempt, so their land survives generation to generation, preserving quiet nodes in the web of Tokyo’s analog urbanism.1

The effect of the inheritance tax on landowners is to encourage subdivision, thereby increasing the supply of housing and other space.2 That makes great sense when there’s a shortage of space, less so when you’re entering an era of population decline. As I wrote here, developers in the post-growth city can still easily realize profits from redevelopment in the short term, but in the long run, Tokyo is likely to have an oversupply of unused private space that will have no social value and cause deflation to seep through the real estate market.

Meanwhile, among the things the government spends its tax collections on are new community centers and programs to ensure people do not become isolated, etc. Wouldn’t a more ideal outcome be to forego the tax collections and preserve properties that already, or could, play a socially beneficial role in communities? Into this category I would place most if not all surviving public baths, but also many other buildings like the seed shop. How about abolish inheritance taxes for cultural properties entirely?3 That would cause a wave of registrations, and the overall effect on urban land markets and housing supply would still be close to nil. You could add a stipulation that properties should be opened up in some way to become part of a new urban commons.

I know that’s a bit utopian. But such a system would produce a more socially optimal outcome for the post-growth city than endlessly increasing its supply of homogenous space that will eventually contribute to the problem of vacancy and devalued real estate assets. The fact that Tokyo does not have a housing crisis now because it built, built, built in the past is not a logical justification for why it should build, build, build indiscriminately today.4 Sure, use Tokyo’s experience to make your point about NIMBYism and the North American housing crisis, but the way space has been produced no longer matches where Tokyo needs to go in the post-growth future. Must we be condemned to be a city without history or community due to our position at the center of commerce, where preservation is never the “highest and best use”?

I wrote about this a bit back in 2021, when I went to stay at Homeikan, the last of hundreds of traditional ryokan that once stood in Hongo, at a time when it was threatened with imminent redevelopment.

Perhaps the disappearance of old ways of life is an unavoidable part of urban evolution, but this process assumes new meaning when extinction looms for the final specimen of some wondrous, endogenous form of architecture. The last reminders of an urban ecosystem that was once open and porous are pushed over the brink by the invasive species of uniform convenience stores, widened roads, and private spaces hidden behind concrete walls. Just a short walk down Hongo Hill to the west, the high-rises of a nearly complete redevelopment that has reaped tens of millions of dollars of public incentives loomed over the roofline of the inn. To the dispassionate administrator, the disappearance of sento and ryokan and the construction of apartment towers is just the natural functioning of urban land markets—there’s no need for the government to intervene due to nostalgic attachment to the past, especially when resident taxes are ballooning thanks to all the well-paid professionals moving in. Yet I have a hard time looking at all the gleaming new skyscrapers in Tokyo in 2021 and believing that people a few decades from now will be glad we poured public funds and social resources into building ever more houses and offices when the city was on the cusp of population decline, instead of preserving the dwindling cultural heritage that made this place unique and tied together its social fabric.

Let me end on a brighter note and tell you that something remarkable happened at Homeikan. Thanks to the tireless advocacy of several of my colleagues, an alternative buyer was actually found at the very last minute, and the ryokan’s three buildings have survived intact. Last week I visited for the first time in three years, and listened to the proprietress in her kimono excitedly tell the story of the mosaic tile floors in the bathrooms, twisted bamboo adorning the hallways, and patterns on the ceilings that I thought I would never see again. Through the agony of so many lost spaces, there’s always the possibility that some can be saved. And there’s still one final seed shop down the road.

Inheritance tax rates are 30% after ¥50 million = $350,000, and step up to 50% after ¥300 million = $2 million. Land prices are much lower in the regions, so people can often pay the lowest 10% rate, but in Tokyo the system often necessitates destroying a building and selling off a portion of the land.

Tangible cultural properties currently enjoy a 30% reduction in the assessed value for inheritance tax purposes. There are only about 13,000 such buildings nationwide. When we helped Inari-yu register, it was one of the first two in Kita Ward. Making the system more generous would hardly impact real estate markets or tax collections.

“But Tokyo is still growing!” Not exactly.

Great article. Maybe there is an opposite acronym to “BANANA” (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything/anyone) that would describe tokyo development.

Fascinating article, thanks. What new building will be taking the space? Here in Kyoto it would inevitably be another hotel.