The akiya influencers have arrived

Japan's vacant houses are now a global social media trend

These days we all live in algorithmic bubbles. Instagram has decided that mine shall be filled only with Japanese houses, a sign of how renovation, craftsmanship, and architecture are among the content best suited for our era of short-form video and photographic media.1 Some favorite akiya (vacant house) renovation accounts include the meticulously documented Kinoma Project in Nagano and Dylan Iwakuni’s gorgeous joinery at his farmhouse restoration in Saitama. I also recommend that you follow this super cool place called, ahem, Labyrinth House.

Nice accounts aside, there is something inherently strange about transforming houses into visual artifacts that float in digital media streams. The defining characteristic of a house is indisputably its physicality, as a space anchored in its environment that we build from materials and inhabit in the real world. When doing my own renovation work, I try not to browse too much—the breadth of content can be useful for finding inspiration,2 but it also distracts from questions that can only be understood in context. Producing content also refocuses the process on how spaces are externally perceived rather than the dialogues taking place with the people, feelings, and objects inside.

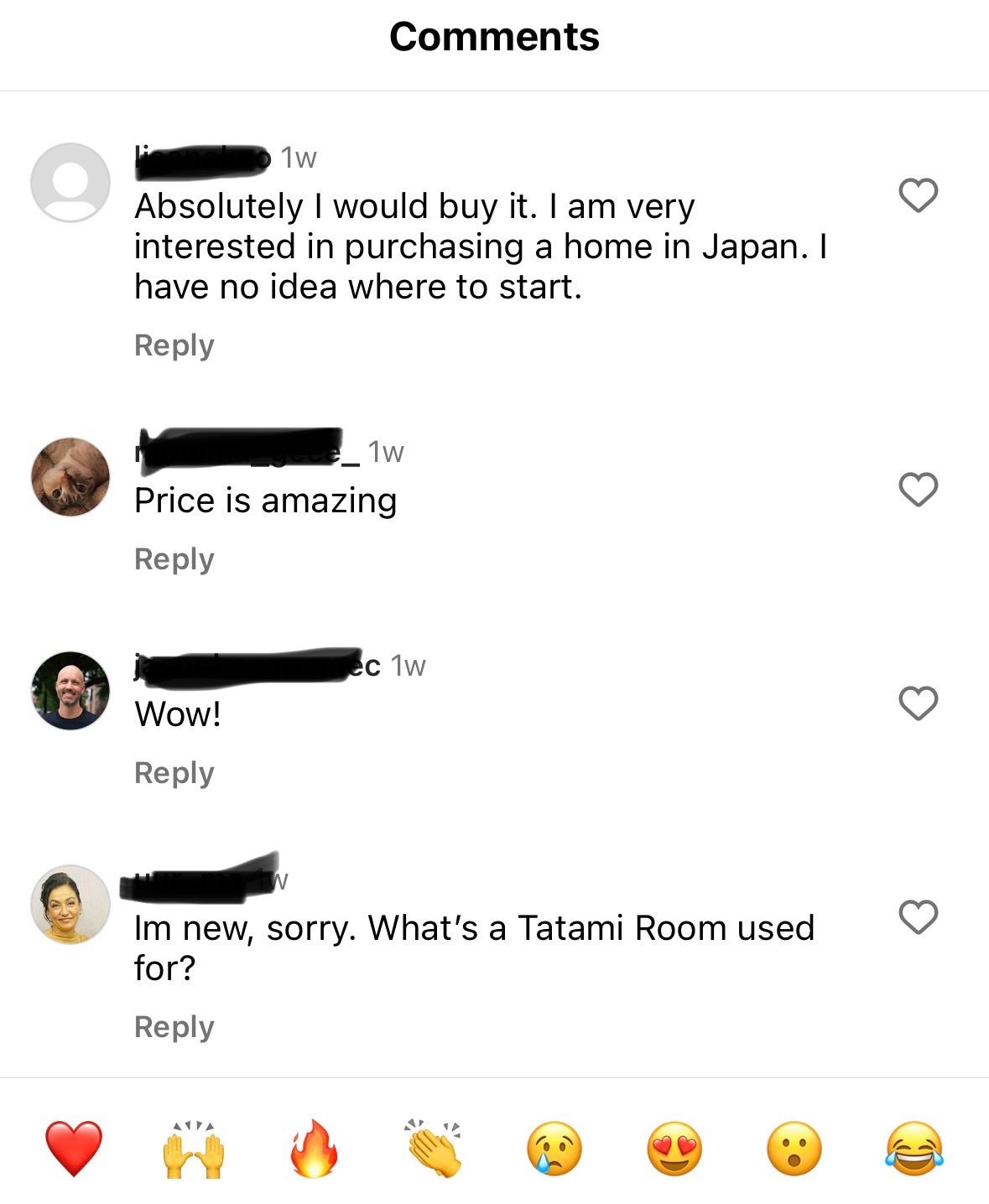

Anyway, occasionally the algorithm shifts gears and tries to see if you’ll bite on content adjacent to your interests. In April I noticed my tiles started filling up with pictures of vacant houses next to prices in USD, and talking heads in front of properties or holding books about free houses in Japan. I was being nudged into the world of akiya real estate and akiya influencers. This was new and intriguing to me, because my akiya content consumption has always been through Japanese media and accounts. Many of these English-language accounts have tens or even hundreds of thousands of followers, some of whom are presumably actually searching for houses. But many of the people consuming and liking this content seem to have no clue what they are looking at, yet are so enthusiastic about the idea of cheap houses in Japan:

Welcome to 2024, when the idea of the “akiya” has been untethered from reality to float context-free around the globe. The discovery of this corner of the internet did help explain why post-pandemic there are more Western tourists who wander up the path next to Labyrinth House and ask “was this an akiya?” Seven years ago when I was writing a master’s thesis about akiya, I doubt almost anyone overseas knew what the word meant.

The first akiya influencer I stumbled upon on Instagram was Anton, who by the time he showed up in my feed had already amassed over 300,000 followers and written a how-to book called Free Houses in Japan last year. He appears to be having a good time churning out vicarious DIY content and offering advice on how to acquire and renovate properties, gaining some traction in the Japanese media in the process. From there, I started tapping through to other accounts and discovered a whole ecosystem of akiya content on English-language social media. Join the four million+ people who have watched this guy’s tour of his $6,000 house in Myoko, Niigata, or the 329,000 followers of Shu Matsuo Post’s account, which mostly features walkthroughs of run-of-the-mill empty houses in inconvenient commuter suburbs of Tokyo.

There’s also a slew of accounts with names like Akiya Mart, Houses of Japan, and Japan Home Quest (it’s an RPG! Item acquired! 🧙♂️💎🏰) that scrape listings from akiya banks around the country and post the photos with a USD price tag and sometimes AI-generated voice-overs. Some of these accounts make money by offering assistance in acquiring real estate, while the best like Cheap Houses Japan (354,000 followers) also run paid newsletters that give their followers tips on good properties. From what I can tell, this content has been exploding since Japan re-opened post-covid, but especially in the past year.

Akiya advice is mostly bad

Let’s start with why akiya content is mostly bad advice.3 Acquiring an akiya could be a good choice if you’re looking to live there full time (I hope you have a visa) or will derive pleasure from devoting tons of time and money to a DIY adventure. But the sort of thing we’re doing down at Labyrinth House requires the right kind of akiya and an understanding of local context, networks and language to be able to do well, which is why I am not out here writing about how “I got a free house in Japan and so can you!” I am also skeptical that most fresh-off-the-plane foreigners would be able to find true happiness by moving to an isolated, disappearing community in the countryside or cramped house in a drab suburb of Yokohama, especially if integrating into the lower-wage Japanese economy forecloses the option of return.

My second source of skepticism stems from understanding that an akiya is not an asset. The dollar price tags on all those akiya listings may suggest the existence of a functioning real estate market, but in many marginal suburbs and rural areas in the post-growth era, there is no guarantee of a future buyer. Akiya exist on the precarious edge of real estate markets, so it is probable that as settlements become socially unsustainable and suburbs more undesirable, you may not be able to offload a house at any price. It is very likely to become a stranded asset—maybe from the moment you buy it.

So if it is not a financial asset, the purchase of an akiya for part-time use as a second home in Japan boils down to the use value. Taking into account renovation & upkeep expenses and inconvenient/unappealing locations of most properties (context that is stripped away online), for a lot of people it would be wise to forget the dream of home ownership and stay in a nice onsen or cheap accommodations in a different region of Japan every time you come.

That leaves a final avenue of practical advice, the one most closely tied to thinking of akiya in terms of money-value: become a post-growth slumlord! (Please do not do this). This seems to be the suggestion of Shu Matsuo Post’s YouTube titles like “Meet the Foreigner in Japan with 96 Tenants and an Akiya House,” “This Foreigner Bought 10 Akiya Houses in Japan,” and “The Man Who Bought 110 Abandoned Houses in Japan.” The supposed arbitrage play is pretty clear: the yen is down 30% (“Japanese Yen is Worthless!” shouts another Post video title) and Japanese incomes are stagnant, so swoop in and snag some cheap properties, put on a fresh coat of paint, and enjoy a nice source of passive income. Tapping into the desire for a passive income can be a rocket ship to social media success.4 Meanwhile, foreign investors in the broader real estate market (ordinary properties, not marginal akiya) are already causing Tokyo housing prices to surge since the pandemic.

This sort of absentee landlordism benefits nobody, but it’s also just terrible financial advice. Post’s videos always include the USD price, a lowish estimate of renovation costs, and the expected monthly rent, before ending with “Would you buy this akiya?” Stripped of context it sounds like a deal, but it’s surely relevant information that the very same suburban Tokyo cities that he visits will see 3-7x increase in akiya between 2018 and 2040.

How well is that investment property going to hold up amid such over-abundance? There’s a reason why the value of these houses is collapsing, and being a foreigner does not give you some superpower to find hidden value where Japanese people can’t see it.5 I expect that ten years from now, there will be many re-abandoned homes whose owners have disappeared overseas.6

Akiya as attention economy arbitrage

The akiya influencers have discovered a good arbitrage play though—it’s just not in the real estate market, but the attention economy. Practical advice is not the reason why hundreds of thousands of people overseas choose to subscribe to walkthroughs of abandoned houses in a foreign country they know nothing about.

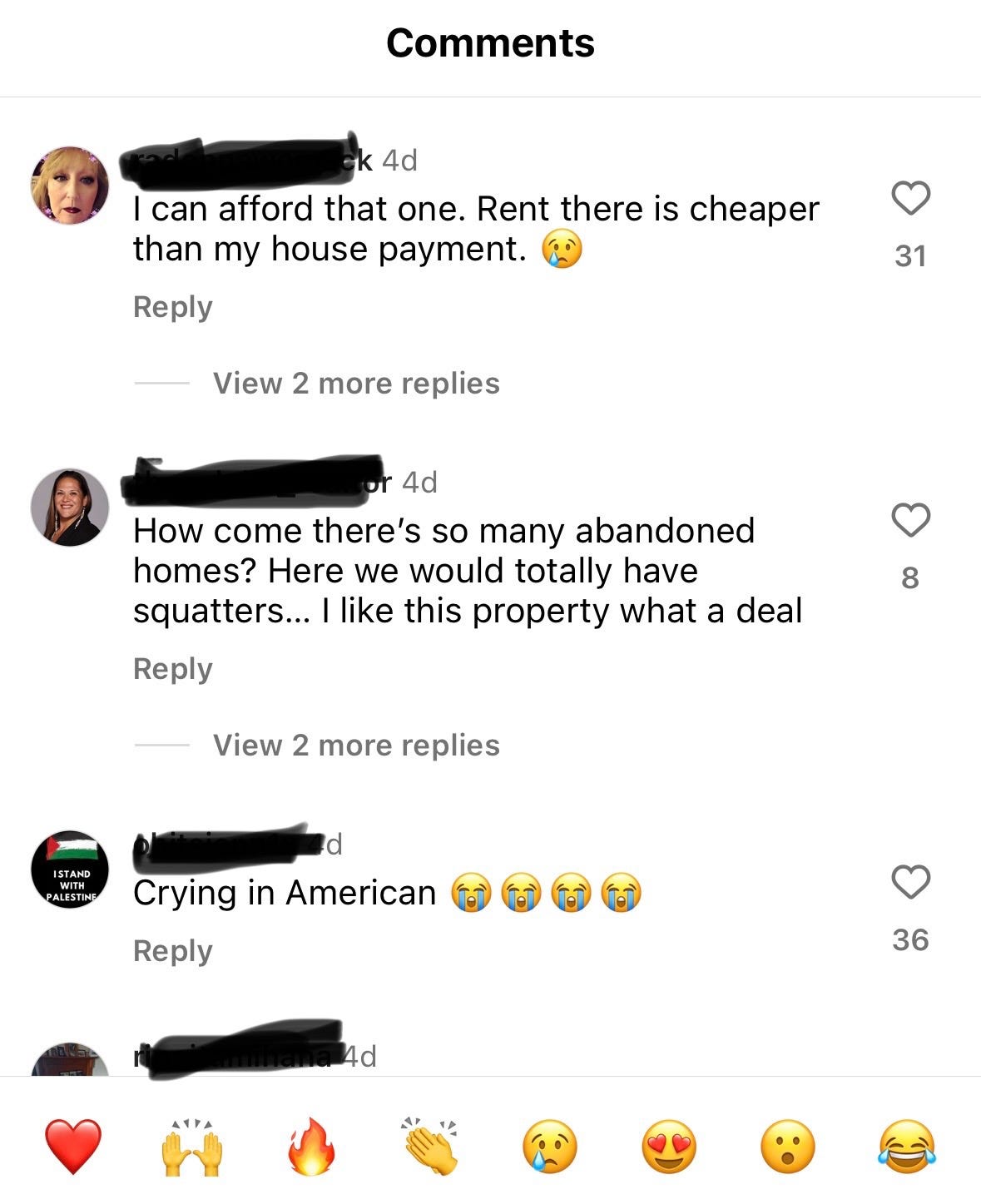

On social media, value is generated by the ability to place decontextualized information in front of people who will be surprised and interested. I imagine that many followers are rent-burdened Westerners who are slowly giving up dreams of homeownership in their cities, look at Zillow too much for their own good, and get served tons of real estate content. Among all the 3-million-dollar listings for subpar ranch houses in Palo Alto, here’s a foreigner telling you that you can get a beautiful farmhouse in Japan for less than a beat-up used car,7 or a decent house in Tokyo for less than a down payment in Seattle or Dublin. What? How? I just vacationed in Japan and loved it! The arbitrage is rooted in the gap of expectations of real estate value, not the real estate value itself.

Seen in this light, akiya content functions as a sort of hentai cousin of the genre of “property porn” where realtors walk you through gorgeous Manhattan penthouses destined to be bought by financiers and oligarchs, or shows like Selling Sunset or The Parisian Agency on Netflix. In its mediated form, the house becomes an unattainable object of desire, a means of escape from the real-world housing dystopias in the places where viewers actually live. And of course, akiya also fit perfectly into the internet’s general fascination with “weird Japan” stories.8

As I was thinking about akiya through a bored online foreigner’s eyes, I recalled taking a college buddy in 2016 to visit some Japanese friends who had recently moved into a free, formerly vacant 70-year-old house in the mountains of Gifu. Over beers in their cozy renovated kitchen, I told my American visitor about the implications of Japan’s demographic future: how real estate markets will collapse in conditions of abundance, and houses would become like natural resources in many places. To which he replied, dude, this town is beautiful. The foreigners will come. The market will not collapse.

Fast-forward to 2024, and I’ve found my own free houses at Labyrinth House. But with a dollar buying ¥160, Japan feeling closer than ever through social media, and other rich countries mired in housing crises, I’m also ready to concede that my friend had a point. The 2020s are the start of Japan’s full-blown population decline. We’re now in the gold rush phase when a lot of foreign prospectors will show up. Many will go bust and leave behind their mine tailings.

This guy slinging mud to a plasterer high on a scaffold is a perfectly crafted dopamine hit.

This video inspired me last month to do a parquet floor from leftover columns in the entryway.

For serious akiya advice, ignore the foreign influencers and hucksters and just read my Labyrinth House collaborator Akihiro Yamamoto’s series here.

Post made his first post about akiya on November 19, 2023 and has never looked back, reaching 100K followers on February 19, 200K on March 21, and 300K on May 13.

Another video claims that a good strategy is to look for flawed properties (訳あり物件) like those next to cemeteries or where someone has died, which have stigma in the Japanese real estate market. To which my only response is, who the heck do you think you’ll be renting to? Even if immigration were no barrier, how many priced-out North American millennials are prepared to move to a 700-square foot house with no yard or parking that’s a 15 minute walk from a station on some crammed commuter line, in a country where they don’t speak the language?

Perhaps I’m wrong, the yen will collapse and Tokyo will become another downtrodden Phoenix cul-de-sac in the global real estate game, while our private equity overlords jet in and out of their ski condos in Niseko.

“Less than a beat-up used car”—to borrow the words of one Hawaiian investor I met this spring who was looking to buy up rural properties.

For another entry in the “weird Japan” houses genre, see this befuddlingly written post on “Japanese nail houses” (aka holdout properties that impede development). Despite the title, precisely zero of the photos are of houses in Japan, and in any case we do not call these “nail houses” in Japan—this is apparently what they are called in China (钉子户)—something the author actually acknowledges. There are many such houses all over Tokyo and Japan, like this amazing one in the middle of the runways at Narita Airport, but the author seems to have no specific knowledge about Japan and instead lifted the photos from this 2014 article titled “China’s nail houses.” Of course, substituting “Japan” for “China” in the title is key to making it viral because on the internet, Japan is where weird things happen. It worked, as Substack actually featured the article in its recommended reads last fall. Likewise, the dream of free akiya fits perfectly within the online imagination of Japan.

🤦♂️

Your're right that markets value these things rather appropriately but one dynamic that I've witnessed in Berlin and that's probably the same everywhere is how myopic locals are to long scale developments. I've had dinners in Berlin when I just got here where the people who already were there all were super convinced that "Berlin has no income base and therefore rents will never increase dramatically here". Locals believe that things will be the way they've always been (or they like to believe that).

There may be a data driven Akiya play here by checking (against population, transit, economy and other sources) which of these areas stand a chance of making it through the downturn and which ones should be abandoned/rewilded entirely.

Anyway, I've felt the tug of this as I've very briefly felt it when seeing the abandoned Piedmontese villages while hiking through (imagine the winters up there…) or the $1 Italian palazzo renovations on TikTok. Maybe some day.