The analog wonder of "Perfect Days"

What a Tokyo film tells us about the urban experience

There’s a moment in Wim Wender’s Perfect Days when a young woman, presumably born in 21st century Tokyo, slips a cassette tape into a car stereo and hears an analog recording for the first time. She appears captivated by the revelation that recorded music can sound more textured and alive, perhaps more interwoven with reality, than the audio she typically streams through her smartphone. A digital native discovers the analog world.

Perfect Days is a film about the attention we pay to the world around us. A more straightforward description was offered by my mom when she first told me about the film in February: “It’s a story about a man who cleans toilets in Tokyo and is perfectly content with his life…so kinda like you.” The designer toilets in question are in trendy & modern Shibuya on the city’s west side,1 but Perfect Days is not really a film about toilets. It is a commentary on the medium of the city itself—how we inhabit and interpret it. Most of the film is set on the east side, where the protagonist lives and my worldview was formed over the last decade, in old neighborhoods like Kyojima, Oshiage, and Asakusa.2 The website gives a good sense of the setting. When you see the narrative as rooted on this side of Tokyo, Perfect Days reads as an ode to Tokyo’s fading analog urbanism.

Analog technology is everywhere in Perfect Days, mediating relationships between humans, and between humans and their physical and metaphysical surroundings, beyond just the murmur of cassettes or a payphone call. The protagonist plays a days-long asynchronous game of tic-tac-toe with a stranger on a folded up, hidden sheet of paper. He buys second-hand paperback novels from an overstuffed bookshop to be read in dim lamplight, and uses an old 90s point-and-shoot and black-and-white film in his quest to capture pleasing compositions of tree shadows.

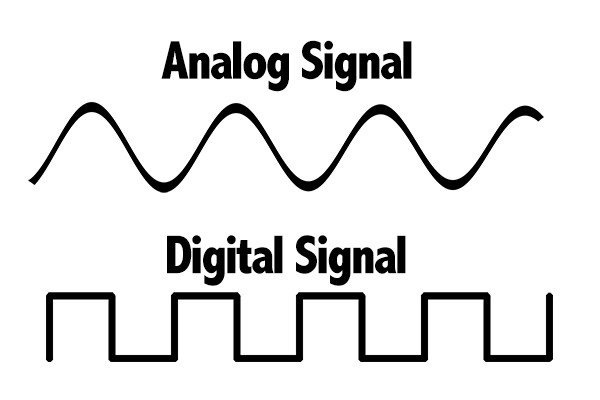

I read all of these details as more than just the proclivities of a technophobic toilet cleaner. Recall the distinction between analog and digital: analog communication occurs using waves that are smooth and continuous. Digital signals, in contrast, are composed of zeros and ones: stepping, square, and discrete. Basically:

Translating this to the context of urbanism and everyday life, I am talking about the difference between a city of porous thresholds and serendipitous encounters versus a city of enclaves and preprogrammed function. An understanding of the self as inextricably woven into one’s social and physical surroundings, thereby able to appreciate beauty and absorb vicarious pleasure like our happy toilet cleaner, versus a discrete individual (consumer) engaging with the world as something external to the self. A lived reality in which attention and feeling is sustained and unhurried, or one in which we toggle constantly between different attentional states and manners of being as if flipping switches from 0 to 1. These differences have everything to do with how spaces are constructed, how we move between them, and the interactions they engender.

The Tokyo depicted in Perfect Days is a thoroughly analog world of places that flow into one another in a continuous, fluctuating medium of experience. In one of the first scenes, Hirayama is awoken before dawn on the tatami floor of his tiny second-floor room by the faint sound of a broom sweeping at the shrine across the street. He lives in one of the once-ubiquitous uninsulated wooden apartments, where the outside can be heard, seen, and felt, and transplanted ferns can be tended next to the big window that looks out at the canopy over the shrine. Upon leaving home, he moves through the city in interludes spent listening to tapes as he loops around the urban core along the metropolitan expressway, or slow tracking shots of his bike coasting through winding alleyways to the bathhouse3 and over bridges to his favorite small bars. The medium of transmission that melds life into a continuous signal is the bathwater that sloshes between neighbors, the light and shadows, the wind rustling the leaves of a shrine, the smiles on familiar and unfamiliar faces that subtly stitch people into reality. To the modern eye, the continuity of his life world has the effect of elevating his habits from quirky idiosyncrasies to a monk-like way of being.4 He appears to inhabit the city on a spatial plane that eludes ordinary people, and yet all he’s doing is being present in mind and body in his environment.

Conspicuously absent are features of the digital city—never does a smartphone or algorithmic suggestion intrude, nor does anyone teleport between places on underground trains. These two technologies have contributed most to the digitization of the urban experience. Via the subway, the city is segmented into discrete packets that are reassembled without context or continuity. The smartphone, meanwhile, makes sustained attention to our surroundings next to impossible, and tempts us to abandon serendipity for the shallow comfort of algorithmic assurance. As the city is digitized, distinctions in physical reality and lived experience are sharpened, between indoors and outside, work and home, me and you, human and nature, online or present, bored or entertained. The “smart city” is not a city; it is something different altogether—an internet in physical form. Most attempts by developers to recreate the analog city can never be anything more than high-fidelity digital facsimiles, with interstices occupied by the cold calculus of commerce from which “intimate living flees,” to borrow the words of Gaston Bachelard.

There is a reason we speak of the city as having an urban fabric. Fabric is continuous, and when it is severed by infrastructure or soulless development, the urban experience unravels. Perfect Days is a reminder that this continuity also extends into ourselves and the intimate spaces of our minds, that among the threads that holds the fabric together is our own practice of inhabiting the city—that to be urban is to be analog.

Here’s a little threshold space I snapped down the street a few weeks ago. Enjoy the start of spring.

The film actually originated as a Uniqlo- and municipally-funded project to promote the gentrification of Shibuya.

Now ten years exactly—I moved to Tokyo on April 3, 2014!

Wenders explains here how he conceived of Hirayama as a monk-like character akin to Leonard Cohen in his Zen monastery years

A wonderful article Sam! Dedigitising my life has become something of a passion for me though I say that somewhat ironically as I sit here typing on my laptop.

The analogue touches you describe and the simplicity of life without digital intrusion sound beautiful. Combine that with my long-standing dream of living in Japan, and you’ve completely sold me on watching the film as soon as possible.

I had fun diving into the comments too. I immediately picked up on the Call Me by Your Name vibes, especially in how people described the stillness and ‘nothingness’ of the film. That quiet, subtle energy is something I particularly enjoy.

Thanks again for the thoughtful recommendation. I’m really looking forward to seeing where it takes me.

I watched this with my mum on her suggestion, and as we were watching it she kept anticipating that something big would happen. I told her I don't think it's that kind of film, but while I was relaxed, she was anxious. its funny how differently we experienced the same thing. I loved it and she was underwhelmed