The path from home to here

Becoming an urbanist by way of Denver, Niigata, and Tokyo

Yomiuri Shimbun published a profile of me in their Tokyo edition earlier this month, for a column in which interviewees talk about where they came from.1 Here it is if you read Japanese:

Telling an interesting story about where you come from really means talking about who you are now and how you’ve changed, so I took the opportunity to explain how I went from feeling at home here:

I started from the beginning: the urban form of Washington Park, the south Denver neighborhood where I grew up. The straight-as-a-go-board street grid, framed by mature oak trees; the City Beautiful-inspired public parks and civic architecture; Old South Gaylord, the little one-block shopping street at the former transit stop in this early-20th century streetcar suburb. From my earliest days, I’d walk the two blocks down there, often with my older sister and her friends, to go to the Soda Rock, a little vintage diner with black-and-white checkered floor tiles and round bar stools that sold bubble gum and pop rocks out of a glass case for a dime or a quarter. An American dagashi-ya! Talking about this in the Japanese context made me realize this wasn’t so different from the old shopping streets I seek out in Japan, and that of all the places I could have been born in America, my neighborhood was the kind where a kid might grow up interested in local communities and urban design.

The reporter asked for a picture, so I chose this shot of my sister Sarah and I in front of our house on Halloween in 1990:

I thought newspaper readers would surely love the very American Halloween scene, but I picked this particular frame because you can see the neighborhood behind us. The bungalows neatly constrained by zoning laws to the centers of their respective plots, the front lawns, the sidewalks, the rows of street trees, the asphalt wide enough to park two cars and pass in both directions—the same as every residential street stretching endlessly in the four cardinal directions! Looking at the photo with the reporter while sitting at the low table in Inari-yu Nagaya, a mere 12 feet away from the house across the narrow alleyway outside the window, this sense of scale feels remarkable and strange in a way that I don’t think most Americans fully appreciate. America is huge! Even urban America is spread out like homesteads on the midwestern plains. You say you have a housing crisis? I could fit a whole Tokyo neighborhood into the space between the evens and the odds on South York Street, complete with a yokocho and bathhouse for good measure.2

I went to middle school in Capitol Hill, and would walk a mile down mildly iffy 13th Avenue to the central library after school to pull maps of Denver’s cow town days from the drawers in the map room. Just as I was becoming fully politically awake, I also grew fixated on urban development. I spent lots of time at the LoDo Tattered Cover and bought books on New Urbanist planning. In 2004, I was distraught by Bush’s reelection, but Denver also passed a transit expansion program, and I dreamt of my city’s transformation into a transit metropolis as I traversed the city by public bus and bike, having disavowed learning to drive (I was an original transit-oriented teen).

At the time, I thought of urbanism mostly in terms of physical infrastructure and tall buildings. I don’t think I was particularly focused on the social or cultural aspects of neighborhood life, and there wasn’t much organic, bottom-up change taking place in strictly zoned areas like Wash Park beyond individual property owners popping tops and maxing out the allowable volumes of their private realms. I imagined becoming a planner and helping to create dense new neighborhoods from scratch along the coming transit lines. In another life, I’d be working on building out RiNo or the River Mile right now.

Coming to Japan

I went to Niigata the same month I turned sixteen. I remember getting my placement packet from AFS in the mail, and opening it up and seeing the city’s name for the first time. I pulled up its page on Wikipedia, and got a jolt of excitement from the aerial photo of the Shinano River emptying into the Sea of Japan. A port city!

There were a few ways in which I think I was extraordinarily lucky with my exchange experience, but the urban environment was one. There were 14 exchange students in the Niigata region my year, and they all lived somewhere out in the suburbs or some of the neighboring towns. Fatefully, I got placed with retired host parents who took an exchange student once and only once, and lived in the oldest corner of Niigata from where I could explore the whole city by foot and bicycle.

Coming to urban Japan was a shock to the system. I wish people could still experience the same degree of disorientation. There were no urbanist YouTubers prowling Tokyo streets, no Japan influencers turning cameras on their daily lives, no Substacks pontificating about the post-growth future. My knowledge of what street-level Japan looked like was mostly informed by the glimpses I saw in Lost in Translation as a 13-year-old. That scene at the end when Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson melt into the crowds of West Shinjuku made my skin tingle in the dark of the Esquire Theater on Downing Street. As the credits rolled I remember thinking, well, that settles it, I’m going to Tokyo!

The environment felt so foreign at the beginning. AFS held a nationwide orientation at the Olympic Youth Center in Yoyogi, with a view of the same Lost in Translation skyscrapers in Shinjuku out the classroom window. I remember my first walk beyond the gates, when a counsellor took some of us out for an excursion across a pedestrian bridge to a 7-11 on a little shopping street in Sangubashi. No sidewalks. Tiny delivery trucks. Pedestrians and bikes going every which way. No street names. No architectural coherence or uniform scale.

Once in Niigata, I initially found the old city similarly confounding. I would walk in one direction for a while and get utterly lost trying to find my way home, looping back again and again until I noticed the turn I had missed.

At the beginning, I don’t think I quite appreciated Niigata on its own terms. The cityscape wasn’t anything like Denver. There weren’t many parks or street trees. I may have even thought that Niigata was somehow less urban than Denver, despite being more walkable, bike-able, compact, and transit-oriented than Denver likely ever will be. After all, it only had two skyscrapers! Denver had forty or fifty. There weren’t big restaurants with patio seating full of young people. The shopping streets near my house were full of little shops selling unfamiliar things amid lots of rusting shutters, and most of the people were elderly. As a high schooler just learning Japanese, most of the neighborhood common spaces, like the bathhouse that was on the corner across from my bus stop (no longer), were too intimidating to enter.

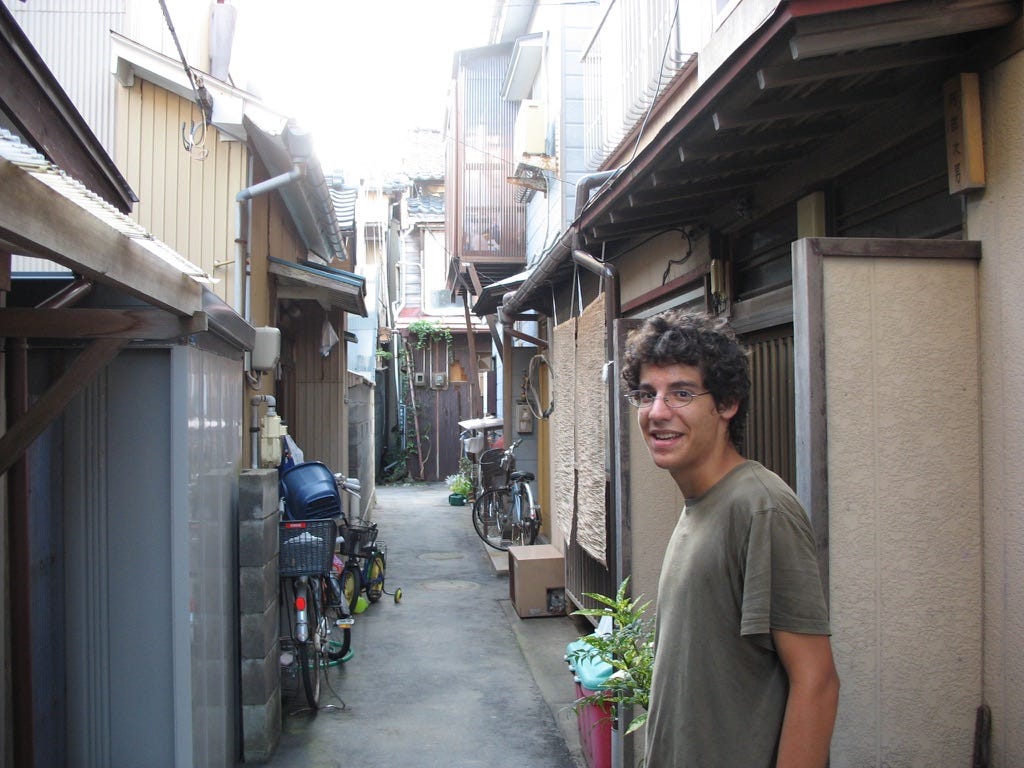

My perspective changed one discovery at a time. I remember one day in the summer, I was hanging out with my Costa Rican buddy Alejandro, who lived a few hours away in Murakami. We were exploring my neighborhood when we stumbled upon a little alley lined by prewar nagaya that was narrower than I’d ever seen before. We ventured in and were astounded to find a whole web of alleys. Niigata had filled in its prewar canals and modernized its traditional landscape in the often bland manner that prefectural capitals do, but beneath the surface, the old city was still full of lots of human-scaled places.

My sense of aesthetics and what makes a great city changed gradually, and not entirely in that first year in Niigata. I was still years away from developing my current frame of mind. But over the years, I came to see beauty not in tidy, planned streetscapes, but in the vernacular forms and organic spaces of local Japanese neighborhoods. In 2014, I moved to Tokyo and lived on $1,000 per month, talking my way into a bunk bed at a share house in the heart of the city, where my monthly rent was $150, utilities included. A few of my nine Japanese housemates helped point me toward interesting cultural trends, art and activism in the urban and rural margins, and I used all the money I saved on rent to travel and learn, eventually encountering public baths, vacant spaces, and post-growth communities like Onomichi.

But that is another story. A decade later, I’m now much more a part of this place than Denver or America. It’s nice to take a look back, appreciate the people and places that made me, and see the threads that I’ve been holding onto from the beginning.

I had intended to write this right after the article came out, but as usual Labyrinth House week #30 got in the way. Coincidentally, Yomiuri was my first employer! Straight out of college, I worked as a local reporter in the New York bureau from 2012-2014.

Perhaps not a winning campaign for Denver Planning Director. But what about parking, they’d say. When I taught myself HTML in middle school, one of the homepages I made was a campaign website for Holden 2028, the first year I’d be eligible for the presidency. A central plank of my platform was a total ban on cars. Sadly I remain a visionary ahead of my time.

I enjoyed reading this, Sam. I arrived in Japan from Europe, via several years in Hawaii, in 1982—when one rarely met non-Japanese even in the very center of Japan’s largest cities. Your experience is as foreign to me as Japan was to you.

Incidentally, that little shopping street in Sangubashi that you mention is where I have been getting my groceries over the past 13 years…