Trains from the past, trains to the future

Where Japan's railways are headed in a post-growth world

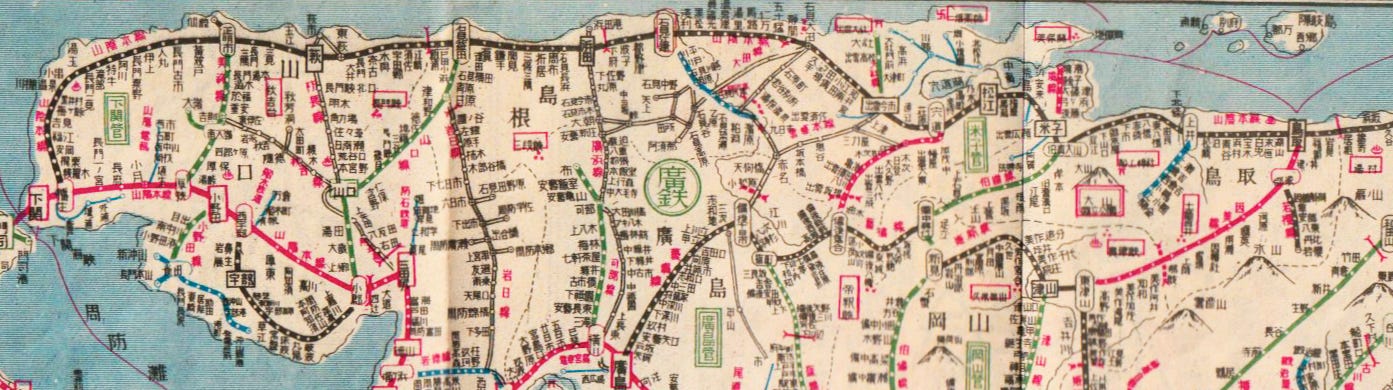

The 1933, the San’in region became the last part of Japan to see completion of its mainline railway, stretching along 674 kilometers of the Sea of Japan coast from Kyoto to the western tip of Honshu. Like railways everywhere, its arrival brought with it the transformations of modernity: national standardized time, national identity, and the national space of an integrated market.

Several weeks after a section of the line opened in Tottori Prefecture in 1907, the town of Kurayoshi welcomed the crown prince during one of his many tours of the realm aboard an imperial train. A notice from the town instructed locals to assemble at the new station by precisely 9:51 a.m., an hour prior to the prince’s scheduled arrival—after 9:52, there would be no further admittance. It was perhaps the first time people there had ever split hairs over minutes.1

Kurayoshi Station now sits in the constituency of Japan’s new prime minister, Shigeru Ishiba, a man known for his abiding love of trains. In a video he posted to social media, his eyes light up as he gushes about the sleeper train that once connected his hometown and Tokyo, which he claims to have ridden a thousand times (considering that he was elected to the Diet in 1986, he may not be exaggerating). For Ishiba, losing his sleeper in the early 2000s was “like losing a lover.” He dates Japan’s decline to the demise of the sleepers, which created a psychological connection between the regions and the capital and enabled movement during the unproductive nighttime hours, sustaining the animal spirits of the growth era.

The rails are where I “think” Japan

Railroads mean many things to many people. On the one hand, there is widespread worship of efficiency and speed. “The Shinkansen […] is the closest we will ever come to a teleportation machine,” wrote the FT’s Leo Lewis on occasion of the 60th anniversary of Japan’s first bullet train on October 1.2 Meanwhile, for the tribe of tori-testu trainspotters, the subtle curves and paint schemes of each trainset are akin to Pokémon to be captured in their natural environment.3

In a long interview about railways last December, Ishiba professes to find both of these fixations boring. His particular strain of trainophilia appears to be not unlike my own—a love of trains not for remarkable velocity or urban complexity, but foremost for how a rail network stitches together the nation into a contiguous spatial and temporal quilt—the intoxicating feeling of passing through the ticket gates knowing the rails can take you anywhere you wish, in a known quantity of time, all while leisurely soaking in everything in between.

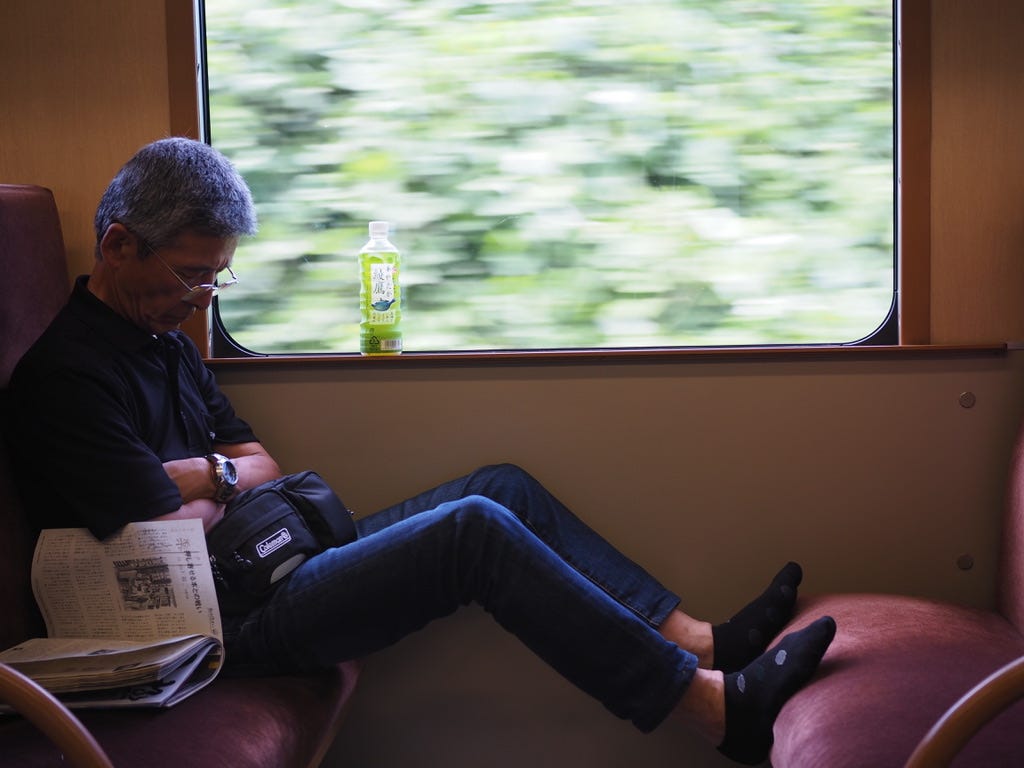

I challenge you to find a better way of “thinking” Japan than booking a private cabin (~$170) on the Sunrise Izumo, Japan’s last sleeper train, which slips free of the haggard commuters on the platform at Tokyo Station at 10:00 p.m. sharp and rocks you to sleep during the 12-hour journey across Honshu, until the sun rises as you trundle through the rice fields and river valleys north of Okayama.

Then, as I did in the summer of 2017, get a five-day unlimited local ticket (~$80) and make your way back. Through 30 glorious hours of window-gazing and reading, plant yourself on benches between an ever-changing cast of factory workers and budget travelers, old ladies going to the clinic and middle school athletes heading home after practice. One local train at a time, watch the country roll past—the towering peak of Daisen, the sand dunes of Tottori, the mountaintop castle ruins of Taketa, the urban constellation of Kansai, the sparkling waters of Lake Biwa, the long, steady climb from Nagoya into the highlands of Nagano, and the quick descent into the pulsating veins of Tokyo as you recalibrate your internal clock to the capital’s tightly-wound tempo.

Riding the rails in such a manner, to borrow the words of the historian Tony Judt, gives me “a sense of regions, distances, differences and contrasts within the limited frame of one small [country]. I think I came to that sense of space by staring aimlessly out of train windows and inspecting rather more closely the contrasting sights and sounds of the stations where I alighted. This is certainly not the only way to come to grips with a society and a culture, but it works for me.”4

Rails beyond growth

All passengers not interested in railway policy, please disembark here 😉

Today, Ishiba’s Tottori is on the front lines of population decline,5 and the railways that were once vectors spreading modernity across the land face an uncertain future. The JR companies would like to shed unprofitable rural lines like those through the mountains south of San’in, where the Sankō Line was closed in 2018 and the Geibi Line is now on the chopping block. Last fall, the government streamlined the closure process for lightly traveled rail segments, many of which have seen passenger declines of 2/3 or more since the 1980s.

Japan’s railways thus face a bifurcated future: on the one hand, the narrow pursuit of speed through the expansion of the Shinkansen network continues, together with minor refinements in the Tokyo area that promise more convenient rides across the metropolis. On the other, reductions of local service, the closure of rural lines, and more severe balance sheets for railway and subway systems outside Tokyo.

Ishiba seems to find this state of affairs problematic:

I have real misgivings about the capital getting more and more convenient at a time when the population is falling, the economy is not growing anymore, and we need to come to terms as a country with over-concentration in Tokyo and the Tokyo region.

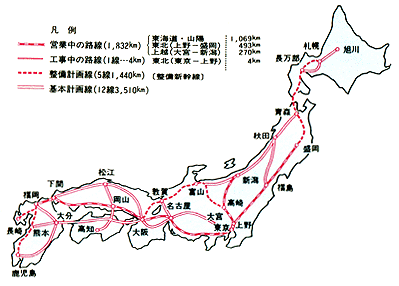

The new prime minister comes from a different political tradition than that of former PM Abe, whose faction has held sway over the ruling party for the last dozen years. Whereas Abe was heir to a legacy that seeks to maximize national power through industrial strength, Ishiba is an idealist whose politics descend from Tanaka Kakuei, the populist prime minister during the 1970s (helpfully explained here by Tobias Harris). Tanaka famously promised to remake the Japanese islands through massive infrastructure investment in highways and high-speed railways, so as to redistribute the benefits of industrial wealth from Tokyo and Osaka to the entire country. His plan envisioned Shinkansen being built to Shikoku, Tottori, and deep into Hokkaido.

Gradually over the past 50 years, five of these new lines have been built. Gearoid Reidy suggests this long-term commitment has served Japan well in comparison to the weak-kneed pursuit of California High Speed Rail or HS2 in the UK, but it seems increasingly unmoored from reality in the post-growth era. In 2018, Ishiba was channeling Tanaka with fanciful calls for new Shinkansen along the Sea of Japan coast from “Aomori to Shimonoseki,” but by last year he had changed his tune:

Tanaka laid out his vision in 1973. It’s been 50 years since then, and by the end of the 21st century, Japan’s population is going to shrink by half. In these circumstances, with the population declining and public finances shaky, does it really make sense to stick with that plan? It’s a wonderful dream, but I’m skeptical about building any more of the planned Shinkansen lines. At this rate, the San’in Shinkansen wouldn’t be done until the 22nd century.

I’ve taken both of Japan’s newest Shinkansen extensions in the past year: the Nagasaki Shinkansen (opened 2022) and the Hokuriku Shinkansen extension from Tsuruga to Kanazawa (opened this spring), which I used en route from Kyoto to the Noto Peninsula in April. In both cases, convenient one-seat express service has been replaced by an incomplete high-speed line that necessitates a burdensome transfer, leaving you to wish the whole thing had never been built.

Completion of the Nagasaki Shinkansen is held up by Saga Prefecture, which doesn’t want to pay for construction when it stands to benefit little from the higher speeds. The Hokuriku extension, meanwhile, illustrates how the Shinkansen has made the country’s rail network more Tokyo-centric: it is now slightly faster (also more expensive) to get from Fukui to Tokyo, but more difficult to travel from Fukui to nearby Nagoya or Osaka. To connect the new line to Osaka, the government has chosen to forego the easiest, cheapest, and quickest route, which would meet existing Tokaido Shinkansen tracks at Maibara around 50 km away. Instead, they’re planning to do what Tanaka probably would have done: 140 kilometers of tracks along the lightly populated coast before tunneling beneath Kyoto and all the way to Osaka, posing a slew of environmental and engineering problems. News broke earlier this year that completion is now expected to cost ¥5.3 trillion ($35 billion; 10x what the route to Maibara was originally estimated to cost), and would not be completed until the 2050s, when the region’s population will be dwindling. The self-evident insanity of this plan has compelled opponents, including some of the local governors, to renew calls for reconsideration of the simpler Maibara option. Perhaps Ishiba will listen?

Maglev folly

The most interesting things Ishiba said in his December interview were about the Chuo Shinkansen, the enormously expensive project to construct a mostly underground, 500 km/h maglev line between Tokyo and Osaka, which would cut travel times in half. In JR propaganda, this wonder-machine is presented as the logical next step in Japan’s journey of growth and progress, “connecting history and creating the future”:

Ishiba let his true feelings about the project slip:

I don’t really understand the point of the maglev. There must be a lot of people who feel this way. When the Tokaido Shinkansen [the bullet train between Tokyo and Osaka built in 1964] was finished, there was a huge amount of criticism of the project. At the finance ministry, they called it one of the three great follies of the Showa era. But at the time, the Tokaido Main Line was operating at capacity, and the Japanese economy was just taking off. It turned out the Tokaido Shinkansen was enormously visionary, but do we really need the maglev? […] I won’t say it’s meaningless, but Tokyo and Osaka will be connected in an hour [instead of 2:25]…a lot of people are thinking, so what?

Here we see the flawed premise of the project exposed: the economic returns on speed have been exhausted. JR can commission as many studies as they want promising multiplier effects in the trillions of yen, but their claims don’t pass a simple smell test. Overworked professionals being able to get to Osaka by 7:07 a.m. instead of 8:25 is not going to turbo-charge the economy (is JR aware that their trains have Wi-Fi now?). Ishiba knows this is bullshit, and presumably so do many people inside JR.

The maglev dream was hatched in the early 1960s. If left to the market, it probably would have died the death of an over-evolved technology whose need has been obviated by more recent developments (see: the Internet, business hotels, low-cost aviation). But the chairman of JR Tokai happened to be one of PM Abe’s closest confidants. The company got shovels in the ground in 2014 with a promise to fund construction entirely with private profits from the Tokaido Shinkansen.6 A few years later, Abe said that for the sake of the economy, we need to finish it faster, and got the finance ministry to dish out ¥3 trillion of interest-free financing (imagine Trump signing an executive order to give Elon a blank check to build his Hyperloop scam). “Wasn’t it promised that they wouldn’t use a single yen of tax money?” Ishiba snarked. “When did we agree to open the public coffers?”

I could write at length about the deep problems of the maglev project, but Philip Brasor has already done that in a quite detailed series of English posts. Suffice to say the company has been lying for years about the timeline and economic viability of the project, and has now yoked the country to a fabulously expensive albatross that will cannibalize the Tokaido Shinkansen’s profits, consume vast amounts of electricity, and worsen the fiscal position of the whole railway system as the population declines. They’re not building social infrastructure; they’re destroying it.

In Abe’s theory of national greatness, it was important that Japan have the fastest, most advanced train. The symbolic projects pursued while he held power strived to restore national strength through the same means it was accumulated in the high-growth era—with a new bullet train, the Tokyo Olympics, the Osaka Expo, and ever-taller skyscrapers in central Tokyo. Only when people saw Japan doing great things again would they regain confidence in the future—those animal spirits that left the station with the sleepers would return, and voila, the demographic problem would resolve itself. Clearly, things have not worked out that way. Perhaps Ishiba will be a figure who pushes past some of this magical thinking to forge the outlines of a new post-growth realism.

Or perhaps not. In his first press conference since taking the reins, Ishiba was asked about his earlier criticism of the Chuo Shinkansen. “I will stay the course of the Kishida Administration,” promised the new prime minister. “We must reap the economic benefit of completing the maglev as soon as possible.”

原武史、『「鉄学」概論ー車窓から眺める日本近現代史』, p.97

In fact, the maglev Shinkansen will come closer to a “teleportation machine”—twice as fast, and almost entirely underground with no scenery to provide a sensation of movement through physical space. Passengers will alight into new, deep subterranean terminals through space-lock like portal spaces to shield them from electromagnetic forces.

Like many Japanese hobbyists, tori-tetsu can be extremely hard-core. Pity a poor 70-year-old man in Tottori who had his blueberry and persimmon trees in a field along the rail line chopped by someone last year. “I saw a tori-tetsu carrying garden shears and an electric chainsaw a few times, he probably cut them so he could get a picture of the express train at the best angle” (Yomiuri Shimbun, May 2024)

Tony Judt, The Memory Chalet, p.71

Tottori is expected to shrink from around 531,000 people today to less than 450,000 by 2045. Ishiba’s district in the House of Representatives, the Tottori 1st, has the smallest population of any district in the country, and in 2015, the entire prefecture had to be combined with neighboring Shimane into a larger district for House of Councillors elections, to address the growing overweighting of its votes. It is the Wyoming of Japan, although the unconstitutional imbalance of voting power that necessitated reapportionment was closer to 3:1, rather than the 80:1 disparity of the U.S. Senate. Darn constitution!

It should be pointed out that these are private profits (about $5 billion a year) generated from the inheritance of national railway assets. It would be just as logical to expect Tokaido Shinkansen profits to sustain unprofitable local lines in Hokkaido and elsewhere in Japan.

Great article, thank you!

Thank you for such an interesting and informative read. I was especially curious about your thoughts on the Maglev project—many seem to share the sentiment that 'overworked professionals being able to get to Osaka by 7:07 a.m. instead of 8:25 isn’t going to turbo-charge the economy.'