We’re well on our way to our Labyrinth House crowdfunding goal. Thank you, readers! If you missed my last post, you can read about the Labyrinth House project here, and make one-time contributions and see construction progress at this page here:

Where do our architectural desires come from? Take, for example, my desire to create a 35,000-tile bathhouse-style mosaic of Onomichi on the wall of the bath at Labyrinth House, complete with a view of the illuminated stone wall outside. Once the thought popped into my mind, I couldn’t really un-think it. The vision became an end that could justify occasional drudgery. Sure, you might be crawling through the dust under the floor right now, I’d tell myself, but someday you’re gonna be sticking tiles on that wall. I had the mosaic vision around two years ago, when the bath looked like this:

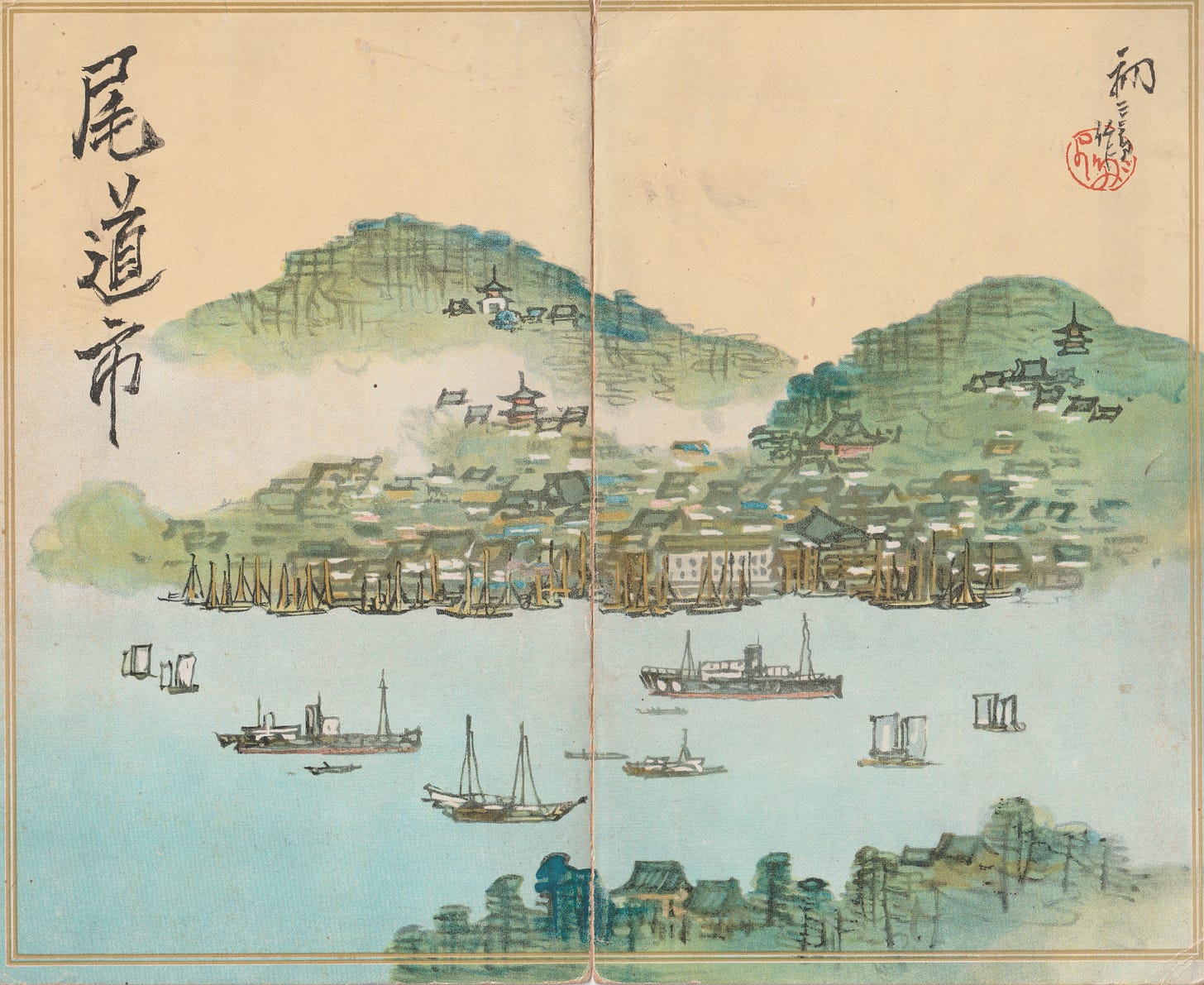

I had recently acquired a panoramic drawing of Onomichi from 1934, which came in a sleeve with the most lovely sketch of the central hillside. It reminded me of the landscape murals that began to be painted on the walls of Tokyo bathhouses in the early 20th century, anchoring these intimate spaces in a larger urban cosmology just as the actual views of Mt Fuji and Mt Tsukuba inscribed in Edo/Tokyo’s layout were being obscured by tall buildings.

I tell you of my dream bath in order to share something about our philosophy of building Labyrinth House. The architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander, best known for his seminal A Pattern Language, wrote a lesser-known volume in 2010 about the construction of a school campus in suburban Tokyo that bears the delightfully grandiose title The Battle for the Life and Beauty of the Earth. A friend gave it to me a few years ago, sensing that my work had something to do with what Alexander calls the “struggle between two world-systems”:

In SYSTEM-A, creation and production are organic in character, and are governed by human judgments that emanate from the underlying wholeness of situations, conditions, and surroundings. This is the primary driving force of every action, and every decision. […]

In SYSTEM-B, the production process is thought of as mechanical. What matters in system-B are regulations, procedures, categories, money, efficiency, and profit: all the machinery designed to make society run smoothly, as if society itself was working as a great machine. The production process is rarely context-sensitive. Wholeness is left out. (Alexander, p. 49).

Alexander writes like Wendell Berry, framing the production of the built environment as an endeavor weighted with much larger spiritual and ecological stakes (“If we smell the dust of a crumbling society, we need to face up to our necessary task, to rebuild our civilization, and to do it well”).

When exactly did architecture become something external to ourselves, mediated by high priests of engineering, finance, and marketing? “One might say, at first blush, that system-B is the product of industrialization, and came from that origin,” writes Alexander. Indeed, there were no “architects” in Japan before the introduction of Western architecture. Of course there were people deeply engaged in the conception and design of buildings, but typically this creative process unfolded as part of the relationship between the carpenter or master builder and their client (seshu). Iconic examples of pre-modern Japanese architecture are usually credited to the seshu, such as 16th century Tai-an tearoom (tea master Sen no Rikyu), or the 12th century reconstruction of Nara’s Todai-ji temple (the monk Chōgen). The emergence of the architect as the most prominent player in the production of space is rather unusual within the broad sweep of world history.1

But Alexander goes on to suggest that “this change in human consciousness is only partially entangled with the industrialization that started in the 18th century”:

It is a much older, broader process, which has taken thousands of years; and over that long span of time has been responsible for the gradual evolution of the human self […] Artists, builders, farmers, and creators were once able to rely on their instincts about materials, location, physical structures […] now as the modern era has unfolded, people’s instincts are more often shaped by external sources — fashion magazines, telling people what they should think about housing, food clothes, accessories, cars — all focused on selling goods. The inner voices, also now shaped by these exterior forces, have therefore become less reliable in terms of well-being, less capable of discerning wholeness, and ultimately less good for the land (p.70).

My experiences have taught me an appreciation for the distinction between system-A and system-B. Traditional building methods bring me closer in spirit to the spaces I’m building, the world at large, the state of being alive, than relying on industrially manufactured materials.

“I don’t care for fads of eco-this or permaculture whatnot,” the craftsman who taught me to build and plaster walls at Inari-yu Nagaya once told me as we worked, “but I care if my materials feel dishonest.” There is nothing dishonest about an earthen wall, solid down to the bamboo lattice at its core, built with materials from the hills and fields outside, smelling of fermenting straw, shaped and cured over weeks and months.

I felt the same way last month, when I went up to traditional carpenter Dylan Iwakuni’s farmhouse in Saitama to help build some walls in his garden. I spent the day stacking heavy river stones, trying to find just the right arrangement of natural shapes to create a sturdy foundation. Others went into the forest to cut and split bamboo, chiseled stone, or shaped the mud holding together the reused roof tiles. The result, made from natural materials and a huge amount of labor, is stupefyingly beautiful:

At Labyrinth House, we have used fewer traditional building methods, and more metal fasteners, styrofoam insulation, drywall and glue than my heart may have liked. Mostly this is a matter of expediency: we only gather for a week at a time, and if we were chiseling tenons for every beam, we would never finish. Of course, we could have gone completely in the other direction of a prefab shower and rough DIY aesthetic and finished long ago. We’re trying to strike a balance between artistry and practicality, living within the limitations of our budgets and time while reaching for something that delights our hearts. We do plan to use some traditional methods: we’ll make the floor of our shop space with a tataki mixture of earth, lime, and bitten, and and we’ve saved old roof tiles to eventually build some dirt walls in the garden like at Dylan’s house. Both will be festive occasions.

But in a broader sense, Labyrinth House is all about practicing architecture as part of system-A: producing space in a manner that springs from context and surroundings, from the malleable social relations that are as much a part of building a place as any wall or pipe. The project thus feels part and parcel of the daily rhythms of waking, grinding coffee and gathering in the garden for morning stretches, sharing home-cooked meals and beer, and pulling out our futon to sleep at night. Over months and years, life can be measured in the visible and invisible structures that hold a place together.

One feature of Japan’s post-growth future could be a renewed flourishing of system-A: the abundance of vacant buildings has lowered financial barriers to DIY projects, and the declining population has put pressure on many building trades, forcing the wider opening of once-closed professions and communities to women, outsiders, semi-pros and amateurs. New channels of knowledge propagation and networks of practitioners lead to what Shuichi Matsumura terms a “democratization of architecture,” after a postwar era in which industrialized processes came to dominate. Sure, system-B will still be churning out mass-produced space and selling us new desires, or achieving futuristic marvels through extraordinarily complex divisions of labor. But for those who want to take leave of this system and try something different, the potential is there. A lot of young Japanese architects and activists are looking at their surroundings and choosing system-A.

How to build a mosaic tile mural

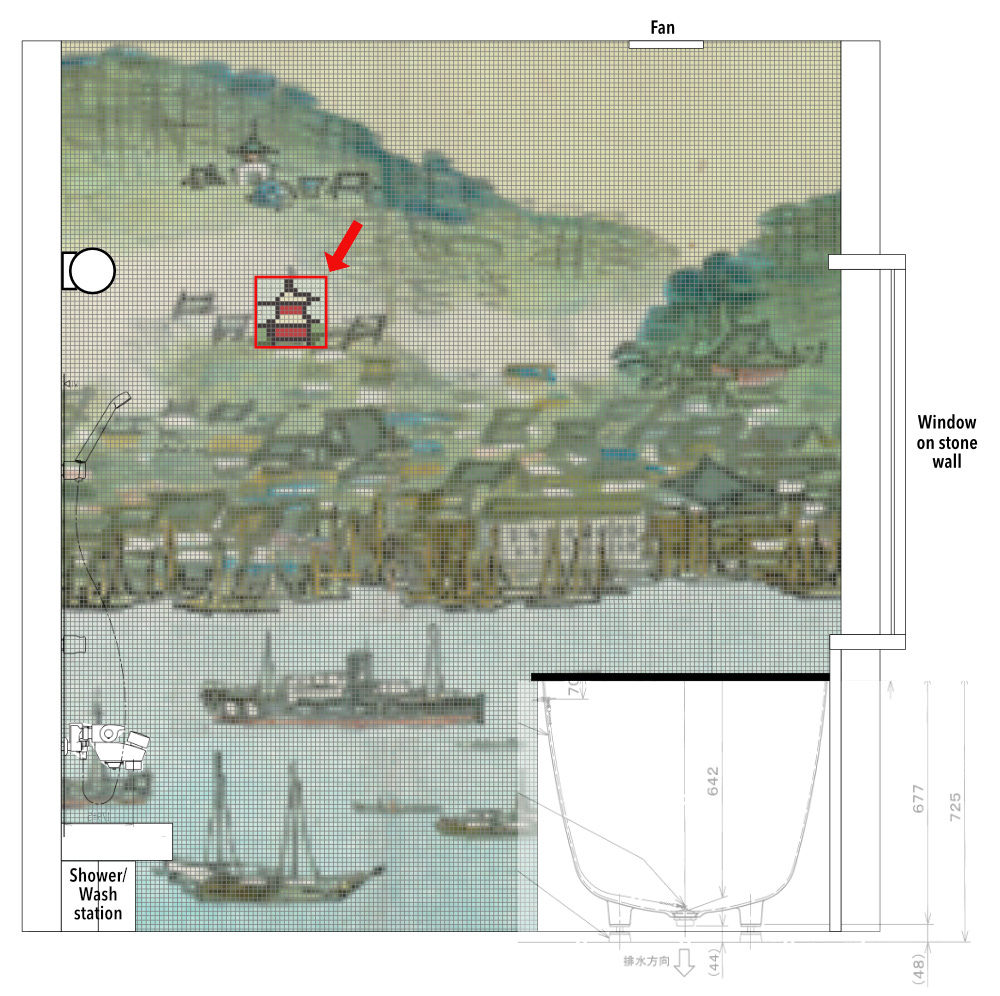

So what about that bath? Obviously, I’m not going figure out the details until everything else is finished next year, but I’ve read some blog posts and have a pretty good idea of what needs to be done once the space itself has been constructed.

First, I pixellate the image so that each pixel corresponds to a centimeter-wide tile plus grout lines (so around 200 h x 200 w). Then I need to simplify the picture into about 12-15 colors, and and make tons of minor adjustments, one pixel at a time, eventually recoloring the whole picture like the pagoda in the red box below:

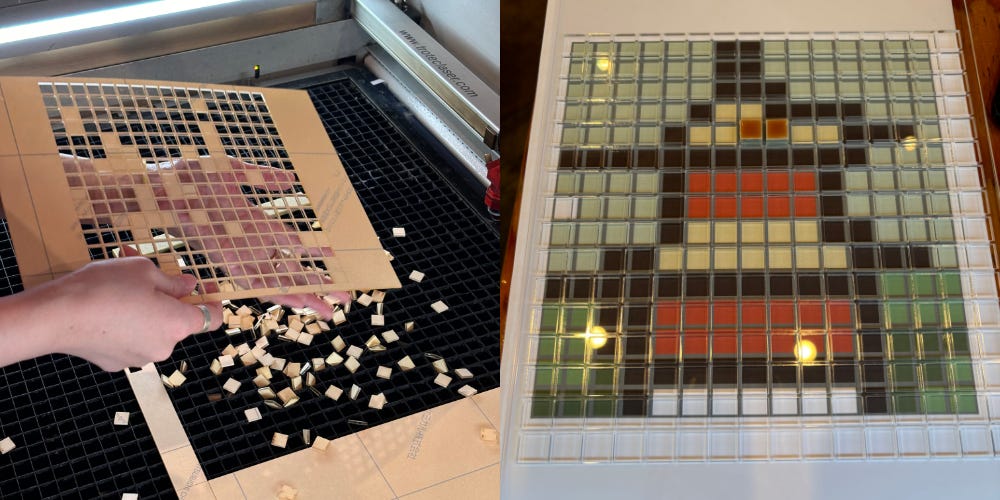

The tiles will need to be assembled into sheets before being glued to the wall. This summer I went down to Shibuya and borrowed a laser cutter to cut a few tile trays from acrylic sheets. It was the first time I had ever had the need for one of those things, but they’re pretty cool! (I’m not a luddite—technology in the service of craft!).

Once the design is finished on my computer, I’ll print it out on A4 paper, lay the trays on top, arrange the tiles one by one, then tape them on the front to create 20x20 sheets that are ready to hang. Of course, that’s just my best guess for how to do it. If you have any experience with mosaic art, I would love to hear your thoughts.

Ever since I became seshu for the second house, my Labyrinth House friends tease me when I insist on taking the more complicated yet purer road. Once we’re done with everything else, Yu says, we’ll need to hold a grand finale—bring everyone together for a weeklong festival of tile arrangement to make Sam’s bath come true. That sentiment is what feels truest about Labyrinth House.

日埜直彦、『日本近現代建築の歴史』(2021年)p.19-20

System A holds a kind of muscular subtlety—precision and toning refined over time, extending life.