What we're building at Labyrinth House

Help us complete our community commons in Onomichi

※ Donations & crowdfunding gifts ※

Our Labyrinth House team is raising funds for our renovation project in Onomichi, to finish the phase two community general store, and get ready for the phase three library. The goal is to raise ¥2 million before the end of 2024 (we are about halfway there!). Whether or not you contribute, I hope you’ll read the project explainer below and follow along with interest. Click through to the page below to make one-time contributions & see the gifts we will send to supporters.

Help us finish Labyrinth House!

—How to contribute

—Gifts for supporters

—Construction progress, 2020-2024

What are you building?

We have been building Labyrinth House for the past four years in Onomichi, a small port city in Hiroshima Prefecture. Labyrinth House is a complex of several early-20th century houses on the beautiful hillside at the center of town, which we received for free and have been designing and completely rebuilding almost entirely with our own skills and money (see before and after photos at the page linked to above).

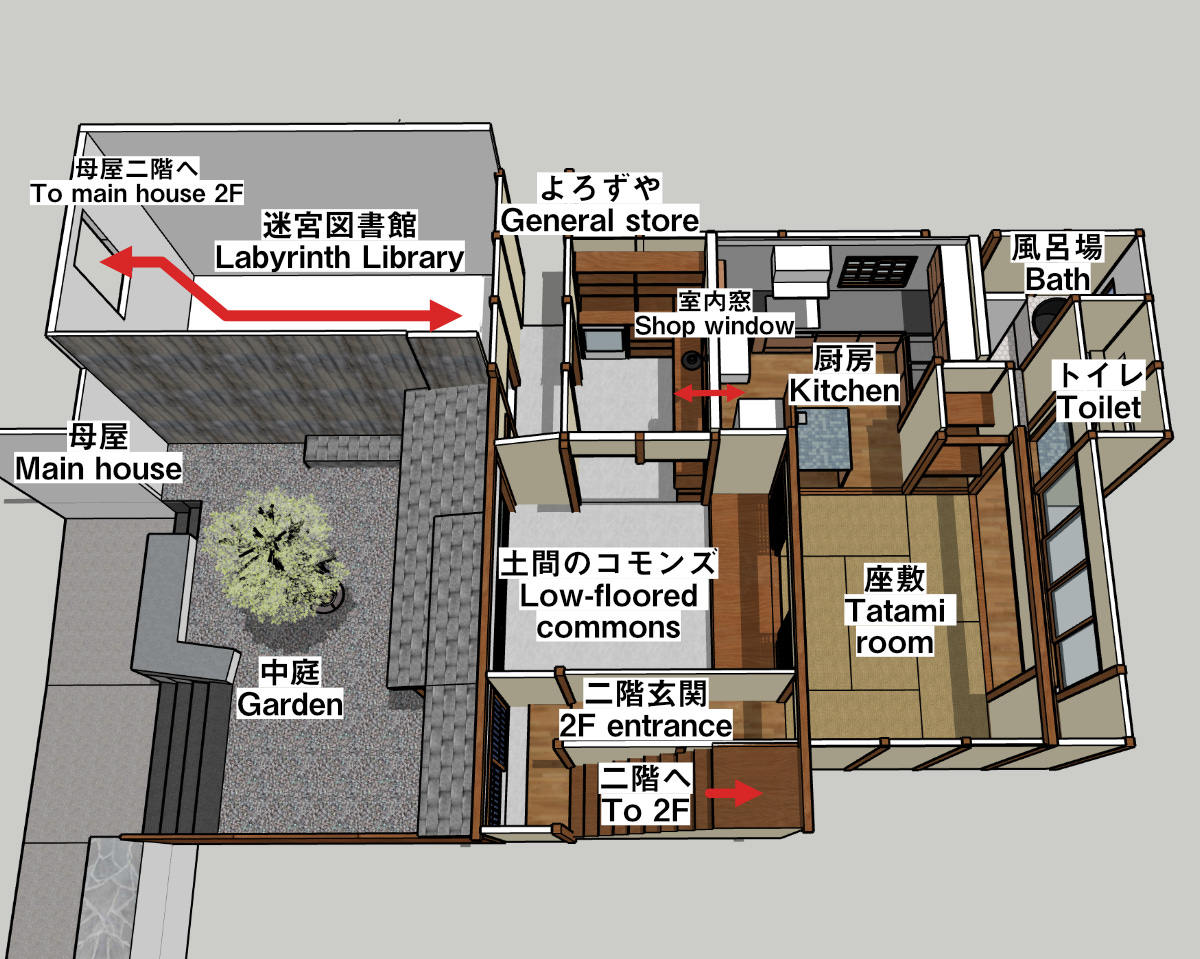

This month we will gather for our 30th week of construction, and expect to finish the second house in early 2025. Labyrinth House is envisioned as a community commons centered on a general store, event/rest space, occasional cafe, library, and mid-/long-term residence. We want to create a place that can support the current community and brings new people and energy onto the hillside in the future. Here’s the plan for the house that we’re building now:

In addition to the community general store (explained below), we’ve designed the space to allow for large social gatherings, screenings and talk events, exhibitions, and other public uses. The low-floored space connected to the garden will be left open most days, creating a small urban commons where visitors can wander in to rest along one of the main routes up the hill. On weekends, members will run cafes out of the kitchen. The second-floor will provide residential space for people involved in the community functions, and serve as an entry point for people migrating to Onomichi.

In the third stage of the project, my collaborator Akihiro Yamamoto will transform our warehouse into a library and local archive. The warehouse’s termite-devastated structure and collapsing earthen walls will be supported from the inside by a complex staircase & bookshelf structure, which will gradually fill up with books salvaged from abandoned houses around Onomichi or donated by residents. The Labyrinth Library will become a repository not only for books, but also history and culture that is disappearing as Onomichi grows older and decays. If we meet our ¥2 million goal, additional money will go toward this phase.

Where is Labyrinth House?

Labyrinth House [Map] is in Onomichi, four hours west of Tokyo next to the Seto Inland Sea. Beloved of writers and film directors in the 20th century, today foreign tourists flock to Onomichi for its beautiful scenery and townscape of cat-filled lanes and lovely renovated cafes.

When I first visited in 2015, I was enchanted by the charming atmosphere, but also the possibilities I saw for producing a different kind of urban space. Onomichi was just the sort of town I had moved across the world in search of: at the time, I was researching the use of vacant spaces in post-growth cities, and had heard stories from activists around Japan of Onomichi and its car-free hillside, where houses cannot be rebuilt, many are abandoned, and real estate is worthless. It has all the problems and potential of post-growth Japan, squeezed into the most human-scale environment you can imagine.

The hillside

Labyrinth House sits right at the middle of this central hillside, a ten minute walk from the station. Climb 150 steps through temple grounds, past some empty houses but also a few cafes, cute shops selling handmade items, and a tiny bakery, and you’ll find the main house standing at a crossroads frequented by a few of our local cats.

To understand this place, consider the following rule of halves: the population of the central districts of Onomichi has declined by roughly half since the 1990s. Only about half of the houses in our vicinity are occupied, half of those are home to elderly residents, and half of those are single-person households. Onomichi, like much of Japan, could thus be said to have a half-life of around a single generation. As people disappear, many buildings slowly return to nature, unless they can change hands and be renovated, re-occupied or reused for other purposes.

The city government and private capital are not committed to preserving the hillside. Yet this landscape is also vital to Onomichi’s identity. Ensuring that it doesn’t disappear in the 21st century largely depends on the efforts and energy of new migrants and local activists, including the local non-profit Onomichi Akiya Saisei Project.1 Labyrinth House is our contribution to preserving this landscape and building a sustainable future for the community.

When were these houses built? When did you get them?

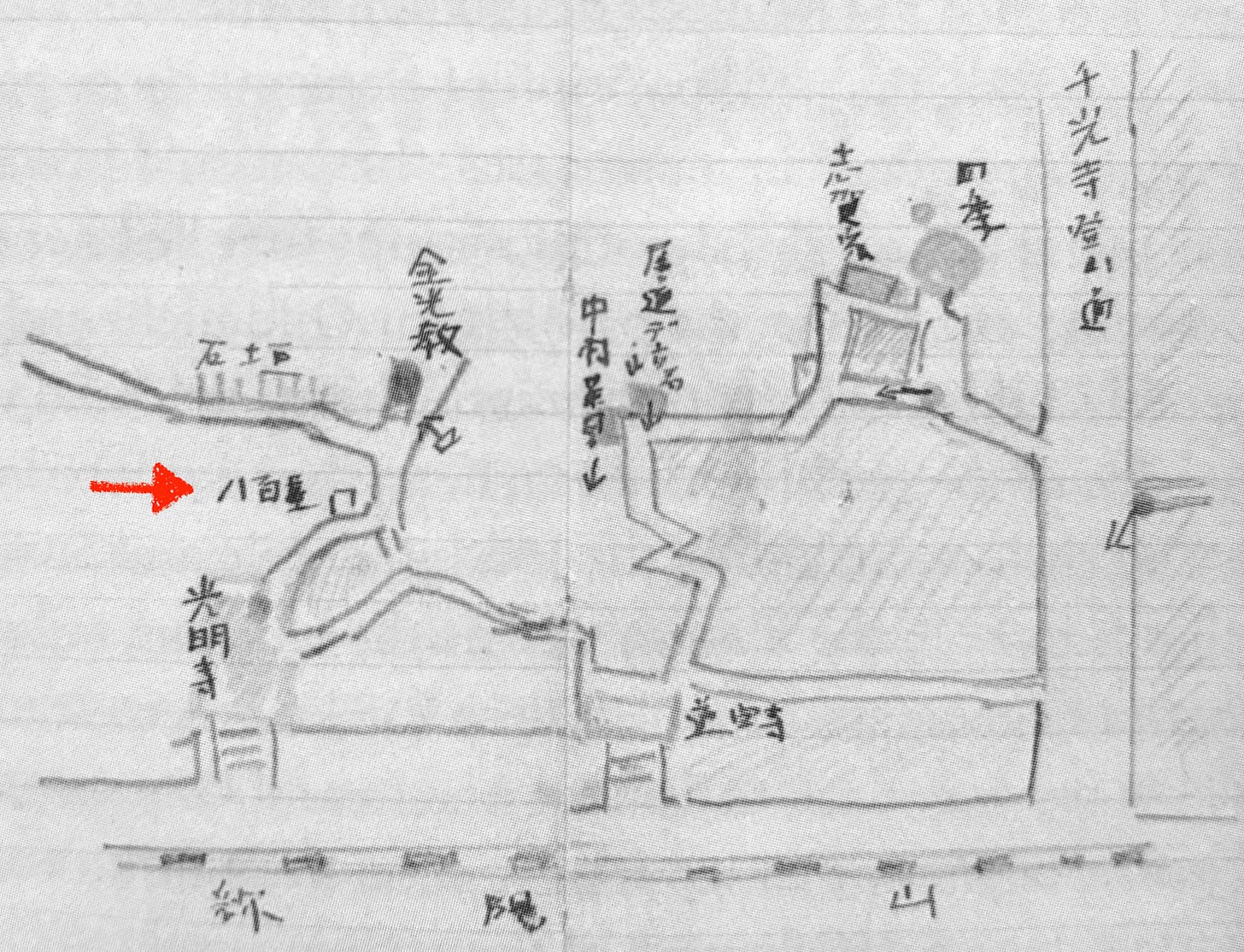

The two-unit row house on the higher end of our land was recorded on the property registry in 1919. It’s on this 1934 drawing, before the main house was built.

The main house on the corner was built in 1937, according to the plaque we found in the rafters. The thick-walled warehouse of unknown age sits between the houses. Many (often ill-advised) additions and structural alterations followed, and eventually the three structures came to touch each other. We plan to connect everything together inside—hence the name Labyrinth House.

The houses, with all their furniture, belongings, and tons of books still inside, came into our possession after torrential rains in 2018 damaged our house and many others on the hillside. The original owners had not lived there for several decades, and after the disaster, their children realized the houses had become a serious liability. Demolition on the hillside is prohibitively expensive, so giving them to us for free was the better option.

My friend Yu Ohtani moved into the main house in 2019. We started renovation of that house in the fall of 2020, and quickly discovered severe rain and termite damage that meant a full structural retrofit was necessary if we wanted to make it last. We legally received the deed in 2021,2 and completed renovating the first house in 2022. Yu lives there now, and the house occasionally hosts talk events and performances.

At that point, we considered taking a break—we were exhausted, and Yu was out of money, but we had developed a special bond and were having the time of our lives. How could we stop!? I convinced the team we should keep going, and decided to pay the cost of renovating the second house. Since then, we’ve maintained a routine of six weeks of construction per year, and now the end (of phase two) is nearly in sight!

Why a general store and community commons?

If earning a return was our primary concern, turning the houses into short-term rentals for foreign tourists would be the smartest option. While I hope to generate enough cash flow to pay the utilities and repair expenses down the road, we are motivated by a desire to do something different—to explore the potential for a space more directly connected to local life.

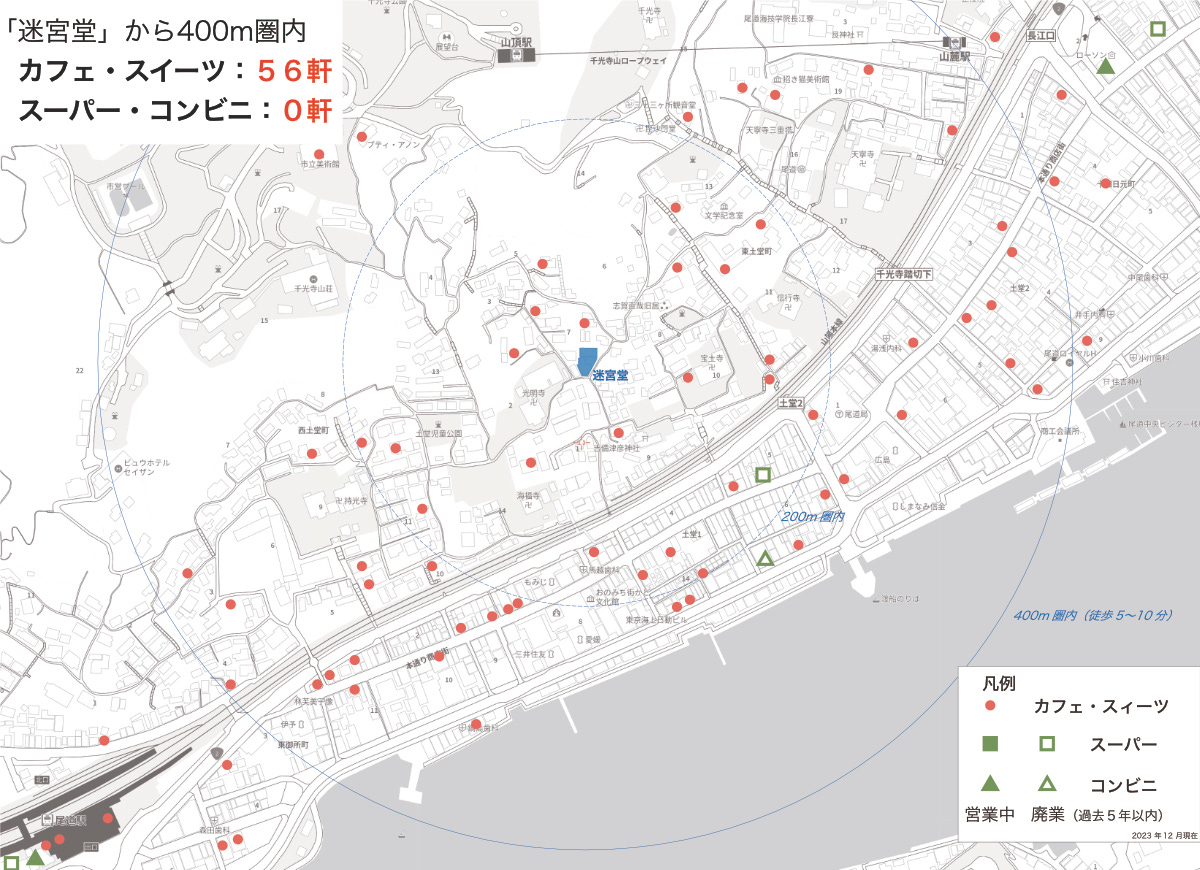

Tourism sustains places like Onomichi economically, but we feel that something vital will be disappear if the hillside loses what’s left of its residential culture. See the map below: there are more than 50 cafes and sweets shops within a 400 meter radius of our house, yet no supermarkets or convenience stores.

That means all those elderly people in the neighborhood have to walk down several hundred stairs and more than a kilometer to the big supermarket to buy anything. A few years ago, Yu polled the local residents about what they would like in the community, and the most common response was a general store. The older locals still remember when this was part of daily life. In fact, there was once a grocery next door to our house! It was prominent enough to be drawn on this location scouting map for the legendary Yasujiro Ozu film Tokyo Story in 1952:

We can even catch a glimpse of this store on the corner in this shot from the 1982 Nobuhiko Obayashi film Tenkōsei.

The house with the fence at the end is Labyrinth House!

Of course, Onomichi has changed. The hillside is no longer crawling with high school students; today it’s mostly old people and tourists snapping photos of cats like our boy Shiro above. So what would a general store that serves the needs of the community today and in the future look like?

Well, we don’t know! Most days the shop space will be open for residents to come in, take what they want, and leave some coins or scan a QR code to pay. Perhaps we will start a system to purchase perishable groceries and goods a few times a month, or let people borrow tools for renovations. On the weekends we’ll host events or serve food and drink in our garden. We’re building Labyrinth House to be a flexible common space like what I’ve created at Inari-yu Nagaya, so it can evolve as we grasp what the community wants and as new collaborators join the project or stay upstairs. Exhibitions and summits will be held. It will be an experimental platform to try to provide new value to the local neighborhood and cultivate connections with other activists across Japan.

Who are your collaborators?

Our core team has been together from the start. Yu and I got to know each other in 2015 over an academic interest in post-growth cities and bottom-up forms of urbanism. He moved to Onomichi after a decade of activism in Leipzig. Akihiro Yamamoto, our construction leader and an award-winning artist, came to Onomichi for college and became one of the most skilled renovators in the city. Then there’s Fu, who showed up for week #1 as an 18 year old who had decided not to go to college. Instead, he’s been learning traditional building techniques, making furniture and art, and becoming part of communities like ours as he has wandered the country for the past four years. Sato-san is a part-time ninja, bartender, and occasional ninja-bartender with a cozy bar in Onomichi’s nightlife district.

Other essential members joined later. After we finish construction, we enjoy feasts prepared by Tacchan, an Onomichi-born chef who wandered onto the site one day when he was between jobs in 2021 and now plans to run a weekend cafe once Labyrinth House is finished. Sho, a pro carpenter from Shinagawa in Tokyo, often hops on the 7:30 AM Shinkansen with me to help when he has time in his schedule, while Wataru moved to Onomichi this year for Labyrinth House after working at a grassroots community space in Osaka.

Beyond this main cast, we’ve had many travelers, young architects, students, friends and others pitch in for a day or a week over the past four years. The beautiful thing about a project like this is the fluidity, how an ever-changing community can be held together around the common task of building and sharing meals together, day after day.

How are you guys building this?

I’m not an architect, nor are any of my collaborators. I use a Sketchup model to think through the design, and draw detailed plans for small sections. But for the most part, we refine the design as we demolish and rebuild.

Knowledge of all kinds trickles down from experienced members to others on the site. As a kid I did DIY projects with my dad, but I picked up most of my skills building Tokyo Little House, Inari-yu Nagaya, and Labyrinth House. When new folks join in for a week, we do our best to expose them to new tasks. We make mistakes and improve. Now on the second house, we’re doing a lot more difficult things than we did the first time around. When we don’t feel confident to make a particular decision, we call up an architect friend who gives us advice, or ask Google.

The most exhausting part of the project is carrying all our building materials up hundreds of stairs. On delivery days we call on local friends for reinforcements. We all eat meals together in the living room of the main house, and sleep together on the second floor of the under-construction house (during the main house construction, we borrowed another vacant house nearby). A project like this is as much about constructing a social community as it is about building a structure.

The first house cost a little more than ¥4 million to renovate. Expenses for the second house have so far have been about ¥3.4 million ($22,400), mostly out of my pocket, along with another ¥2 million or so of related expenses (mostly transport & tools). I’m doing fine as a freelance translator, but it’s still quite a bit of money for me. I think we need about ¥2 million more to finish the second house, and still more to complete the library. I hope you will consider helping us turn this dream into reality!

Final word

Thanks for reading! I hope you visit sometime. I will write more about Labyrinth House in coming weeks, and am eager to kick off a series of essays about the islands south of Onomichi. Week #30 of Labyrinth House begins November 18—please follow along on Instagram! Remember, instructions for how to contribute on this page! 👇

Help us finish Labyrinth House!

—How to contribute

—Gifts for supporters

—Construction progress, 2020-2024

If you are coming to Onomichi to visit, the best way to learn what makes the city special is to stay in one of Aki-P’s renovated guest houses, Anago no Nedoko, along the shopping arcade, or Miharashi-tei, up on the hill. Or, if you have more money and are staying for more than two nights, rent the beautifully restored Gaudhi House.

We split the deed six ways, which means I am a 1/6 owner of three houses and a warehouse. The ownership of the property is not important, as it has no financial value as an asset.