Why the post-growth megacity still gets redeveloped

If Tokyo is a post-growth city, why is it chopping down Gaien's trees to build towers?

The controversial redevelopment of Tokyo’s Jingū Gaien appears to be moving forward despite protests that have attracted attention since the beginning of the year. Gaien is a large park-like green space, home to the national stadium used for Tokyo’s TV-only Olympics in 2021, and has been targeted for development since the mid-2000s by many of the corporations involved in bringing the games to Tokyo.1 Under the final scheme, renewal of the underutilized public space is coupled with an up-zoning of the perimeter for commercial development, including 195- and 180-meter towers, as well as the demolition and reconstruction of a historic stadium and the felling of nearly a thousand trees and plants, some a century old.

The protest movement has attracted the support of luminaries like Ryuichi Sakamoto and Haruki Murakami,2 as well as tens of thousands of ordinary citizens, who have banded together around a “save the trees” message. But setting aside the specific issues (read this), I think this project is also a good opportunity to see the forest for the trees and pose a broader question: why is this sort of thing still happening in the post-growth megacity? Although I might not condone it, I could at least understand if a growing city decided it should encroach on some of its precious green space with high-rise commercial development. But in a post-growth era, shouldn’t we reach a point where this sort of project no longer makes sense to either the developers or the citizenry?

Anyone in Tokyo today knows that the Gaien development is far from an outlier. The city is in the middle of a boom of mega-developments—Japan’s tallest building was just finished last week! A skeptic might reasonably look at the massive skyscrapers going up in every district and conclude that calling Tokyo a post-growth megacity is premature—the growth machine sure looks alive and kicking. But recognizing that Tokyo is already in the post-growth era is crucial for assessing the risks and opportunities it faces.

The city as a spiky bucket

We need a model for understanding how redevelopments like Gaien relate to the macro system of the post-growth megacity. Let’s start with a thought experiment. One way to think about Tokyo is through its spikiness. Here is a spike map of the population density of the metropolitan area (roughly 40m people) rendered in three dimensions:

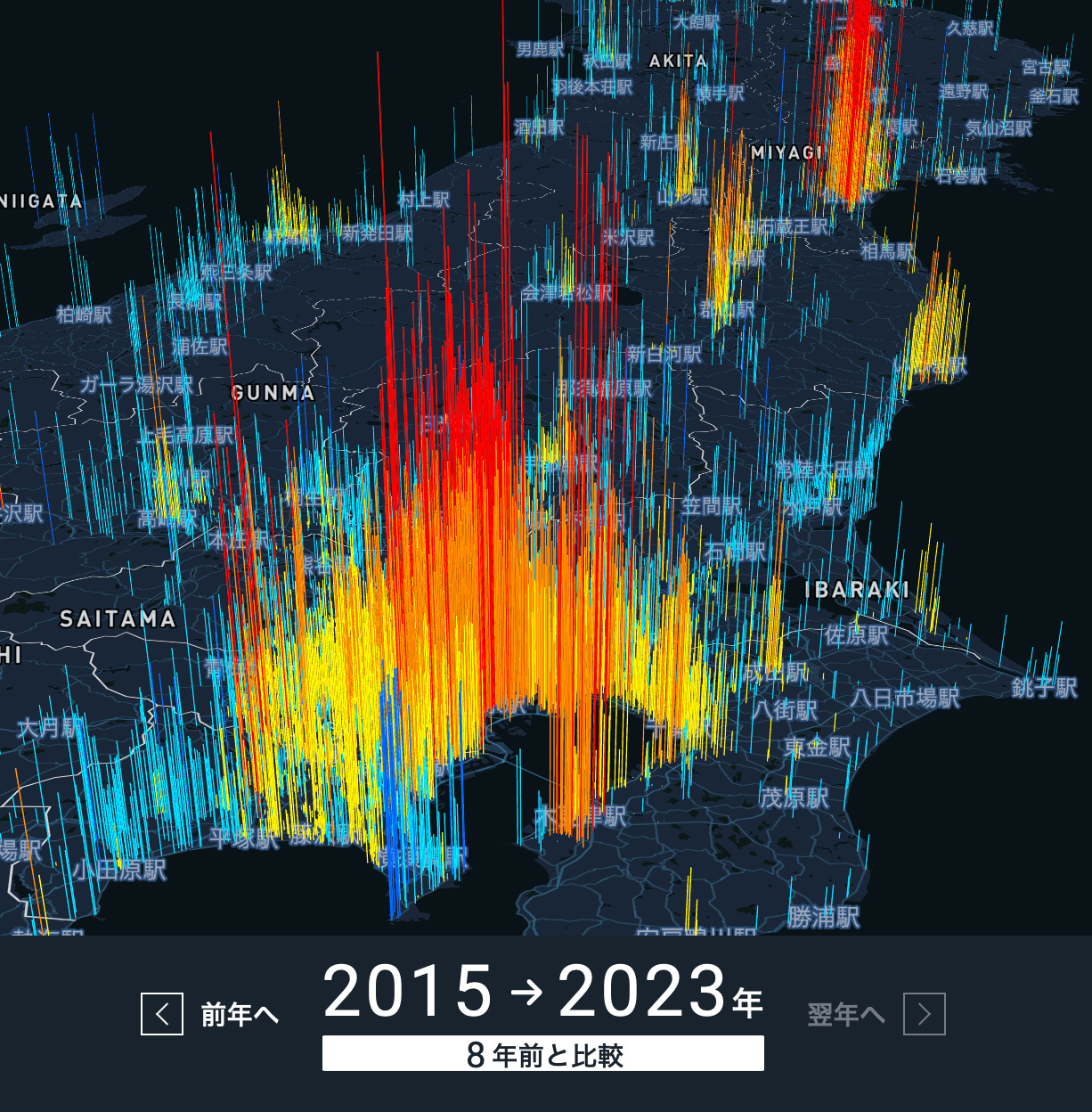

Next, here’s an interactive map that shows the change in real estate prices, shown here from 2015-2023.

And of course, Tokyo is also very physically spiky, with dozens of urban cores and high-rise districts like Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Toranomon clustered around its enormous transit hubs.

This physical spikiness extends to the local scale, like near where I live in Bunkyo Ward, where you can see mid-rise apartments lining arterial roads that sheath low-rise pockets of quiet, car-free streets filled with housing and shops, as well as undeveloped land such as temples, cemeteries, and parks.3

These are representations of the demographic, financial, and physical spikiness of the city. It’s not hard to come up with other ways the city is geographically spiky that are harder to find clean data for: the distribution of consumption, flows of commuters, proximity to urban services, etc.

Now, for the sake of this thought experiment, imagine we can meld all these specific measures of spikiness into a generalized variable that I will call “urban intensity.” I understand that each measure of spikiness does not completely correlate to the others, but for now let us simply agree that the area around Shinjuku Station has a higher urban intensity than, say, a smaller activity center like Kagurazaka or Aoyama, which in turn has a higher intensity than a residential area in Sendagi, which is more intense than a suburban tract of Koganei. You get the point.

Now, imagine we have a beautifully detailed 3D model of the whole city’s urban intensity, parcel by parcel, sitting on a table. The spikiest places are where people, consumption, and built infrastructure converge, typically close to train stations, tapering off to lower elevations in areas with less transit adjacency or farther out from the urban core. Next let’s make a mold of this model, flip it upside down, and fill it with water. Viola, now we have our spiky bucket!

Here are a few things to know about this spiky bucket:

Water can be added from outside the system by a faucet above the bucket, and will leave the system if it springs a leak.

The bucket is made of an infinitely malleable material. Redevelopment to a higher urban intensity means pushing the bottom of the bucket further down. Water flows into these deeper depressions, increasing the capacity of the bucket.

If depth is “urban intensity,” we can think of the volume of water above a parcel as its “urban energy.” Much of this energy can be captured and valorized by whoever controls the underlying piece of land. If you are a profit-seeking developer, your interest lies in increasing the depth of the parcels you control to capture more of this energy.

Here and there, you will notice there are shallows or islands, many directly adjacent to the deepest places: this is land that cannot be developed under normal circumstances, like shrines, parks, or Jingū Gaien, or, the biggest island of them all smack-dab in the middle of Tokyo, the Imperial Palace.4

In this thought experiment, we imagine the bucket representing the Tokyo metropolis, but it could just as well represent post-growth Japan as a whole.

With our spiky bucket in hand, we can now move on to think about Tokyo’s postwar development as occurring in four quarter-century phases.

Four phases of urban evolution in Tokyo

1. Reconstruction & development of the urban core (1945-1970)

In the first phase, the bucket is shallow and overflowing. 55% of the prewar city that once housed seven million people has been burned out, and the housing shortage runs into the millions of units. Moreover, the faucet is on full-blast, as returned evacuees and repatriated soldiers flood in and erect barracks and black markets, followed by a baby boom and waves of rural migrants who crowd into tenements in the 1950s and 60s. Tokyo is desperate to push the bottom of the bucket down as fast as possible. Housing, transit, commercial zones—everything is built in a frenzy, and rebuilt again to higher intensity in the 1960s. This process culminates in the years around the 1964 Olympics, with opening of new transport systems, modern buildings, sewers, and other infrastructure.

2. Expansion to the periphery (1970-1995)

As the relentless overflow starts to ease, it is decided that rather than driving the bottom of the bucket even lower (Tokyo is already uncomfortably dense), it would be better to expand its circumference. So Tokyo sets about building new towns in Tama and opening commuter lines to Chiba and Saitama and engineering double-decker bullet trains to ferry salarymen from Gunma; it makes master plans to redistribute back-office functions from the core to satellite cities like Yokohama and Makuhari and build futuristic new CBDs atop landfill in the bay, and in the process pushes the envelope of the megacity to the edges of the Kanto Plain.

During this phase, the center of the bucket becomes less deep in some places: after 1970, the population of the 23 wards falls by 900,000 to fewer than eight million. But the bucket’s overall volume expands fast enough to accommodate the still-significant amount of water pouring in through the faucet.

3. Redevelopment of the urban core (1995-2020)

Tokyo’s mind-boggling real estate bubble pops in 1991. The bottom of the bucket lurches violently upward, and countless trillions of yen flow over the rim and are lost into the abyss. Take a look all these negative blue spikes as land values plunged between 1991-2006 by as much as 90% from their peak. What an epic disaster!

The authorities, faced with a financial morass that threatens to drag down the whole city’s economy, decide they need to let lenders get bad loans off their books and make the real estate market liquid again, so they make it easier to drive deeper spikes into the center of the bucket by deregulating height restrictions and offering financial support for developers to remake a ton of central-city districts into modern high-rises.5 The bucket stops getting wider, but lots of places in the center get deeper. After 1995, the 23 wards start gaining population, growing by nearly two million to 9.7 million by 2020. Of the some 480 skyscrapers over 100 meters tall in the central city today, three quarters have been constructed since the 2000s.

Lifestyles shift, too. Sayonara to the suburban “My Home,” hello to a 2LDK condo in the core, better suited for double-income couples with one or no kids. While the burst of the bubble marked the first financial hiccup in the growth spigot that feeds the bucket, the demographic transition to smaller family size is more serious in the long term. In 2010, Japan’s population starts to decline, and throughout the 2010s the metropolis’s growth begins to taper off towards zero, even as central Tokyo absorbs a greater share than the suburbs.

4.Dawn of the post-growth megacity (2020-20??)

In our post-Olympic, post-covid moment, the demographic tap that has fed postwar Tokyo has more or less run dry. What’s more, the bucket is starting to leak. In 2022, Tokyo proper lost population for the first time since the urban core began to rebound in the mid-1990s, and the metropolitan area lost population probably for the first time since the war. The leak is small now, but getting bigger.

Worried leaders think, can we open up some new taps? Immigration and inbound tourism? What about chasing Chinese investors who want to dump money in offshore luxury condos? Or maybe we can just keep priming the pump with more and more money? At the very least, the new skyscrapers make us feel like we’re staving off our demise.

Such efforts might inject more urban energy into the system, but can never approach the impact of the postwar demographic boom, rural-urban migration, and Tokyo’s march towards affluence. The growth machine lashes around, scrounging for a drink, but if we zoom out from Tokyo to a national or planetary scale, just how sustainable is opening new taps in the demographic and ecological context of the 21st century?

As redevelopment continues to drive new spikes deeper into the bottom of our bucket, shallow areas get shallower. Existing real estate is devalued and population and economic activity flow away from more marginal areas. Dry patches start to appear inside the bucket: shuttered shopping streets and vacant houses and housing blocks where real estate value has evaporated due to lack of market demand. Post-growth Tokyo becomes spikier than ever.

The growth machine begins to eat itself

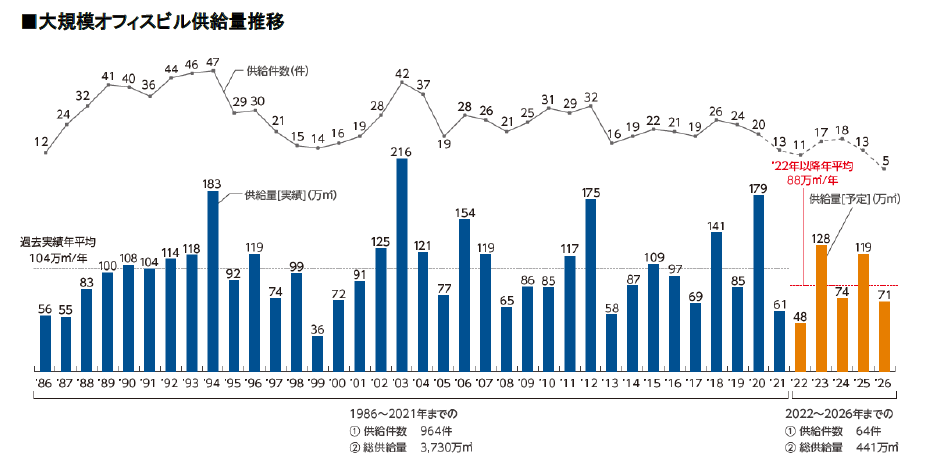

Eventually, I expect Tokyo will wake up to the limits to its growth, and when it does, it will likely have a substantial hangover of overdevelopment. If you walk around the city right now, you can see a ton of mega towers going up. This year’s new supply of large offices is expected to be 1.28 million square meters, the fifth-highest amount in the past twenty years, and this already causing problems. Real estate media has taken to calling this glut the “2023 problem,” and the combination of demographic decline and changes in leasing patterns in the post-pandemic city may make it into more of a turning point than previous gluts (eg. most notably 2003).

The uncertainty in commercial real estate is illustrative of how maintaining the growth machine in the post-growth metropolis becomes a zero-sum game. When the water was flowing, driving the bucket’s bottom downward anywhere contributed to the overall goal of keeping the water from overflowing, but now it just lowers the water level a little for everyone else. But it’s also not hard to see why redevelopment projects will remain perfectly profitable for decades to come. The enormous amount of water sloshing around in a metropolis of 35 million, at the center of a country of 120 million, makes for an extraordinarily dynamic real estate market. If you make it easy enough to sink deep spikes in the right places, molecules will always flow from somewhere else in the system, and a lot of energy and profit can be captured.

Remember, developers are not thinking about the city as a whole. They care how floor-area ratios and prevailing rents and construction costs pencil out as a business proposition on a particular plot of land. Thus a slew of mega-projects in Nihombashi, Shibuya, Tamachi, Tsukiji, Shinagawa, and Mori Building’s fiefdom in Minato Ward are in the pipeline well into the 2030s, even as population decline accelerates.

This tendency towards overdevelopment under the neoliberal mode of deregulated urban development becomes a systemic flaw in the post-growth era. The metropolis begins to eat itself, just as Tokyo has fed itself for decades by sucking energy from the rest of the depopulating country. The profits of new developments are paid for in the declining rents for older buildings, and the bustling restaurants of Shibuya shopping malls are filled with bodies that no longer pass through shopping streets in Nerima. I’m not here to shed a tear for declining asset values, but in such conditions, why doesn’t the government shift course? Why don’t citizens demand a post-growth urban vision?

The short answer, of course, is that the government is committed to ensuring the continued profits of the corporate real estate conglomerates, and full employment. The benefits to politicians from continuing to make it easy for developers to exploit local conditions for profit are tangible, while the macro-level externalities that arise from overdevelopment (eg. social and economic strains in declining areas) are distributed across local jurisdictions and can be addressed after the fact by subsidies ultimately financed with the national debt.6

Tokyo continues to run on a scrap-and-build mentality. The construction and real estate industry, and now also the inbound tourism industry, depend on constantly rebuilding the city. We need to articulate mechanisms of urban governance, and a model of a healthy city, that do not depend on its constant top-down transformation by developers.

So what is the post-growth metropolis to do?

This is, in a nutshell (or bucket), the reason why Tokyo can be both a post-growth metropolis and a city undergoing relentless redevelopment at the same time. It is why developers look enviously upon untouched shallows like Gaien, because the potential payoff for encroaching even a small amount and driving a deep spike nearby is so large. Some will look at this situation and wonder if this is really so bad. It certainly beats a recession! And compared to many ill-conceived projects in the go-go days of the 1980s, developers nowadays are better at seamlessly integrating carefully designed buildings into surrounding transit infrastructure (see Shibuya, Otemachi, etc.), or using projects to revive underutilized urban spaces (see the upcoming Nihombashi River restoration). Sleek and more appealing design has become more important because slapdash projects will sink with the city as the water level decreases. Developers must differentiate their new districts in order to compete for a finite number of office tenants, or convince potential condo buyers that their development and their district will withstand the inevitable downward pressure on asset prices in the post-growth future.

Maybe we know in the back of our heads that at a macro level what we’re doing doesn’t quite add up. Sometime in the 2030s, when the impacts of population decline begin to show on the surface, people may look up at empty office towers and at the vanished character of old neighborhoods, or the commercialized bustle of Gaien, and lament that a lousy, wholly unnecessary trade was being made in the present. Sure, deeper areas are probably more efficient and produce more GDP, but the deeper the water, the more than everyday life and local networks tend to get tossed around in the churn of commercialism. We grow more alienated from an urban experience reduced to a two-sided coin of work and consumption. I like my cities to have more depth, to be full of spaces of genuine human connection and community, and the unmolested nature of places like Gaien. Tokyo’s brilliance lies in how its depths and shallows are intertwined.

So if our goals are social well-being, ecological sustainability, and disaster resilience, as developers like the Gaien project’s Mitsui love to profess, why are we still doing this? We should move towards an economy that nurtures the urban ecosystems that already exist, allowing Tokyo’s emergent qualities to shape the city organically from the bottom up, rather than continue to impose top-down templates for how its residents should live. Endangered urban heritage and human scale should be protected by dismantling growth-era tax and planning systems that force their destruction. Infrastructure investment should flow towards slow mobility like trams and bike lanes instead of more roads for cars. In many cases, organic forces will lead to greater urban intensity around activity hubs. Dry patches will emerge in corners of the post-growth city. There is no need to prevent urban change. But the system should no longer actively incentivize mega-developments that gobble up the city’s urban energy simply as a way to keep the economy churning.

It is distressing, seeing the last-ditch nature of the Gaien protests, to know that electoral politics still offers no hint of the post-growth vision Tokyo needs to thrive in the next quarter century. So aside from dreaming of political change and protesting misguided plans, what is one to do at this particular moment? If you are interested in small-scale change like me, I would suggest you begin by swimming away from the deepest spots in the bucket in search of the shallows. As the water drops, plant your feet in a margin of the metropolis, or a depopulating corner of the country. When you find a place where it’s easy to move and gather with others in meaningful ways, plant a garden and water it with enough energy to thrive, but not so much that it will drown. Assert your right to the city, imagine a community, and enact it. The post-growth city is full of possibility.

I followed this post up with another here.

The Gaien redevelopment predates the idea of the Tokyo Olympics. In 2004, the advertising giant Dentsu circulated a proposal entitled “GAIEN PROJECT: A 21st-century Forest,” featuring new stadiums and a slew of towers. Attracting mega events including the Olympics was listed as one of the goals of the project. The next year, Governor Shintaro Ishihara embarked on the ultimately unsuccessful bid for the 2016 Games, which was reworked into the 2020 bid in which Gaien played a central role.

Gaien’s current redevelopment is not a follow-on effect catalyzed by the Olympic Games; rather, the Olympics were from the start a justification for the pre-existing intention of developers such as Mitsui to remake the city. The same pattern is evident at the Olympic Village site in Harumi on Tokyo’s waterfront, which finally occupied a plot of landfill that had sat undeveloped since the end of the bubble, after being constructed by the government at great expense.

Haruki Murakami once operated a jazz bar down the hill from Gaien in Sendagi and became a novelist after an epiphany on April 1, 1978, while watching a home run from the stands of Jingu Stadium, the historic stadium that is slated to be destroyed.

Google Maps pro tip: in 3D mode hold down control and click to change perspective.

People once quipped that at the height of the bubble around 1990, based on back-of-the-envelope extrapolation of real estate prices in neighboring Marunouchi, the Imperial Palace was worth more than all of California. But of course, it could not be developed.

Privatized profits and socialized externalities—the neoliberal way!

That bit about Tokyo eating itself just as it ate the country is accurate and depressing at the same time.

Thanks for ending with something hopeful. Making our new version of the city at the margins is where folks interested in community, quality of life, sustainability, creativity, etc... should gravitate to. So much is possible when we get out of that deep deep water.

Well but isnt it also one of the amazing features of Japanese cities that development in "mature" areas in fact does happen and therefore the offerings are more competitive and affordable? So maybe the developers and buyers should decide, when enough is enough? Compared to let us say London, SF Bay Area etc, where Real Estate owners and Nimbys capture all the value of economic growth in recent years?

Not to confuse with the continued waste in "public works" projects in Japan...