Why we founded Sento & Neighborhood

Public baths made Tokyo what it is, and are needed to save its soul

A month ago, I explained the thinking that informs my akiya activism, so here I will try to lay out the motivations behind my sento work.

—

Last November I joined together with five colleagues in Tokyo to establish Sento & Neighborhood, a non-profit organization committed to saving some of Japan’s rapidly vanishing public baths, known as sento, and the neighborhoods to which they belong. We incorporated the organization after receiving a grant through New York-based World Monuments Fund to restore and revitalize Inari-yu, a historic bathhouse built in 1930 in the northern Tokyo neighborhood of Takinogawa. WMF selected Inari-yu as part of its 2020 Watch List of endangered cultural heritage around the world, and funded our proposal to preserve and enhance the role of the bathhouse within the local community for the next generation. Along with restoration work of the bathhouse itself, we are using a portion of the grant to construct a new community salon in an abandoned, century-old, two-room nagaya tenement located adjacent to the bathhouse.

I began attending sento soon after I arrived in Tokyo in 2014, just when I was starting to intimately grasp the spatial structure and feeling of the city. Seeking them out became a reason for me to fill in missing patches of my mental map and learn the social geography of Tokyo through observation in the tubs, dressing rooms, and alleyways of the old city. Sento often survive in pockets spared from redevelopment and gentrification, where life still flows along the well-tread paths of the past. They sit on back streets across from liquor stores and barber shops, light trickling out from their open entrances into the evening darkness, beckoning to the unwashed. Inside, a cross section of the local neighborhood, young and old, strait-laced and deviant, gregarious and muted, strip naked and soak together.

These unusual, mostly forgotten spaces became an experiential and conceptual lens through which I learned to see the city. Bathhouses were a refuge during graduate school as I read through the literature of urban geography, sociology, and anthropology and stitched together different concepts of urban space in my mind—commons and thresholds, margins and heterotopias, social production and rhythms. This learning reinforced a sense that in so many dimensions—historical, social, architectural, geographical—sento had played a central role in forming Tokyo’s distinctive mode of urban life, and continue to reflect an essential piece of the city’s soul.

Although the Japanese practice of communal bathing has roots in religious ritual more than a millennium ago, and the dense commoner districts of Edo were home to hundreds of public baths known as yuya, the sento of modern Tokyo are a legacy of the city’s two successive waves of growth after the disasters of the 20th century. During the rapid rebuilding and urban expansion after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the end of the war, Tokyo’s population swelled with migrant workers from rural Japan, especially the northeast, who crowded into cramped living quarters in wooden tenement buildings, usually with shared toilets. The ubiquitous bathhouses—more than 2,500 at their peak—were located every few hundred meters in most residential neighborhoods, contributing to making Tokyo a spatially egalitarian metropolis where low- and high-income housing often existed side by side. Most of the time, a bath formed the center of a little urban microcosm—a tofu shop, a fishmonger, a place to share beers or have a bite to eat—synchronizing the rhythms of local neighborhoods to the tune of daily perspiration.

As I got to know the city’s bathscape, I also watched it be destroyed. There are now fewer than 500 sento left in Tokyo, down from 700 when I arrived seven years ago. My two favorite bathhouses where I live in Bunkyo Ward, Tsuki-no-yu and Kikusui-yu, closed in 2015. That was when I got to know Kuryu Haruka and Sammonji Masaya, now my colleagues in Sento & Neighborhood. As we made futile efforts to save these sento, we learned about the many factors that conspire to make preserving bathhouses at a late stage so difficult: the wear on structure and equipment, lack of heirs, familial disagreements, inheritance taxes, not to mention the decline in visitors as surrounding neighborhoods change. It is no surprise that sooner or later, many aging proprietors relent to the constant calls from developers eager to get their hands on large plots of land where they can erect luxury apartment complexes. A plot of land under a sento in central Tokyo is usually worth at least a few million dollars, so without government or charitable organizations stepping in to save these public goods, scrap-and-build is usually the only game in town. Piece by piece, Tokyo’s urban commons is lost.

Having seen the same story unfold so many times, we were genuinely surprised when we finally got our chance to do something at Inari-yu. We met the owners of Inari-yu when conducting a survey of the remaining bathhouses in Kita Ward, an area of Tokyo that mostly lies to the north of the Yamanote Line and is thus somewhat cushioned from the intensive redevelopment taking place in the central wards. One of Tokyo’s few remaining prewar sento built in the shrine-like miyazukuri style, Inari-yu was already well-known for its frequent appearances in film and on TV. We offered to help the family that runs it to research and submit an application for registration as a tangible cultural property, a category of historic designation that at the time only one other bathhouse in Tokyo had. During that process, we were told about the World Monuments Fund’s biannual Watch List. We submitted our documents after an all-night session in March 2019, and six months later were pleasantly surprised to find our humble Tokyo bathhouse listed along two dozen other sites around the world, including Notre Dame and Easter Island.

Amid so many true “monuments,” WMF included Inari-yu in part in recognition of the value of bathhouses as a vernacular form of urbanism and architecture intertwined with the social life of Tokyo’s communities. Inari-yu is not just a remarkable building on its own, but survives alongside a traditional residential neighborhood in Takinogawa, where narrow alleyways meander between small wooden houses, and local shops line the Edo-era Nakasendo road. The human-scale cityscape remains relatively unchanged since the area urbanized in the 1910s and 20s, having by a stroke of luck avoided the rain of American firebombs that erased most of the surrounding areas. A historic bathhouse in a neighborhood still largely untouched by gentrification, Inari-yu is an ideal place to try to create new connections between sento and neighborhood—and lucky for us, happened to have an abandoned nagaya next door.

The Inari-yu nagaya was built just after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 alongside the nearby Nakasendo road, and was relocated to its current site alongside the sento a few years later, where it served as a residence for employees of the bathhouse in its heyday. Although communal bathing is no longer a hygienic necessity, we want to find new ways that the sento might serve the social needs of the neighborhood. In the renovated space, we envision a community salon that tells the story of Takinogawa and offers people a place to rest and relax after a bath, and where we can involve a variety of people in running one-day cafes and shops, or holding classes, events, and groups that could bring together a wider slice of the community—the families that live in nearby high-rises, or people from a bit farther away who don’t regularly attend the sento. At least once per month, we want open the bath in the morning and serve a breakfast of omusubi rice balls and tonjiru soup.

We began refurbishing the main bathhouse building last winter. We replaced the canvas of the Mt. Fuji painting above the baths and held a public event so the community could watch the painter, one of the last of his kind, create a new rendition of this Tokyo sento tradition. We cleared the nagaya of debris and various things that had been stored away and forgotten, and began refurbishing the parking lot area alongside the bathhouse, which we will turn into an outdoor space where we can also host events.

At the end of May, we began to dismantle the nagaya’s decaying walls, ceiling, and floors in earnest, with the help of a group of a dozen community members and friends. Structural work will take place this summer before we move onto interior work, fittings, and furnishings in the fall and winter. For me personally, this project feels like a culmination of what I’ve been working on for the past few years, taking cues from the urban history-focused space that we built at Tokyo Little House, and challenging me to apply the more advanced carpentry and design skills that I’ve developed at Labyrinth House over the past year. It’s the first time I’m taking the lead not only in design and construction, but also planning the financing and programming as well. Needless to say, it’s great fun and a great learning experience.

While we’re excited to be creating something for the future, every time we hear about another bathhouse closing, we are reminded that the city as a whole is moving in quite the opposite direction.

After wrapping up the first day of construction on May 29, I and the other Sento & Neighborhood members relocated a few kilometers south to stay the night at Homeikan, the last ryokan in Hongo. Ryokan stand alongside sento as architectural gems that are testament to the remarkable skills and creativity of traditional craftsmen. Homeikan operated three buildings in the neighborhood, the earliest of which dates to the Meiji Period. Corridors are adorned with sculpted bamboo posts and wooden screens with silhouettes of spider webs and mythical kappa creatures. Each guest room features not only a unique tokonoma alcove, but a different ceiling design, some with geometric tessellation, the most impressive in the shape of an unfolded sensu fan. The inside, outside, and intermediate realms are permeated by rays of light, the sounds of footsteps, and the fragrance of the breeze. Sitting by the second-floor windows or the garden side veranda, listening to the birds and the voices of children playing somewhere down the street, one feels rooted in a specific historical place and seasonal moment in time. Sadly, after more than a year of muddling through the pandemic, Homeikan had announced it was ceasing operations and potentially closing forever at the end of May, so we were among the last people to have a chance to stay.

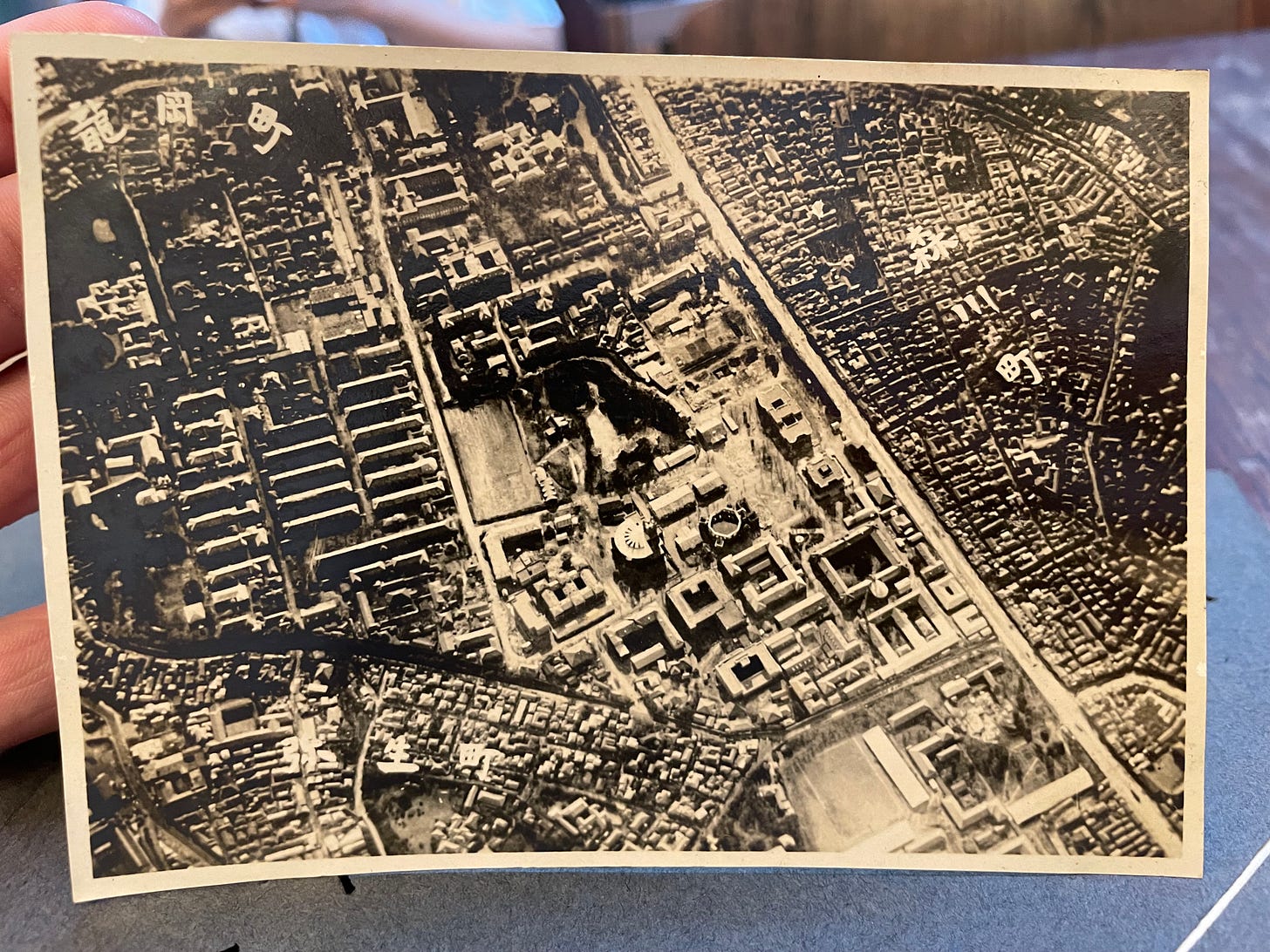

Hongo is home to the University of Tokyo, and in the days when it was known as the Imperial University, some 200 lodges across from the campus served students and travelers. Last week, I stopped by a professor’s house for tea, and she showed me an old photo album of the university that recently turned up in her family’s closet. Inside, a remarkable aerial photograph probably taken in 1926 showed the reconstruction of the campus in a Western-inspired layout of gothic buildings after the Great Kanto Earthquake. What caught my eye, however, was the latticework of donut-shaped buildings occupying nearly the entire neighborhood across Hongo Boulevard in the upper right corner. Each was an old ryokan or geshuku student house built around an interior courtyard—suddenly, I could imagine the streets described in the pages of Meiji-era novels. As late as the 1960s, this section of town still had at least seven bathhouses.

In 2015, we watched as the last bathhouse in Hongo, a lovely place called Kikusui-yu, was demolished and replaced by apartments. I used to live at the top of Kikuzaka slope, and would walk down once or twice a week until it closed. The bathhouse used to bring together both the elderly residents and students who lived in cheap share houses, like me, or old back alley walk-up apartments, like my colleague Sammonji-san. Today, the neighborhood’s remaining wooden buildings have mostly been cleared away for luxury apartments or houses seemingly hermetically sealed from the neighborhood outside, filled with well-paid office workers who enjoy the 6-minute subway ride to the Marunouchi business district. There are fewer places for students to live, and when students do step off the campus, many now congregate in the four or five corporate-recruitment “career cafes” that have sprouted on Hongo Boulevard, where they have to show Todai ID in exchange for free Wi-Fi and drinks. There is no need to venture beyond their social bubble to interact with the surrounding neighborhood, and Hongo’s old coffee shops and book stores fade further into decline.

Six years after saying goodbye to the last bathhouse in Hongo, we were now bidding adieu to the last ryokan. Perhaps the disappearance of old ways of life is an unavoidable part of urban evolution, but this process assumes new meaning when extinction looms for the final specimen of some wondrous, endogenous form of architecture. The last reminders of an urban ecosystem that was once open and porous are pushed over the brink by the invasive species of uniform convenience stores, widened roads, and private spaces hidden behind concrete walls. Just a short walk down Hongo Hill to the west, the high-rises of a nearly complete redevelopment that has reaped tens of millions of dollars of public incentives loomed over the roofline of the inn. To the dispassionate administrator, the disappearance of sento and ryokan and the construction of apartment towers is just the natural functioning of urban land markets—there’s no need for the government to intervene due to nostalgic attachment to the past, especially when resident taxes are ballooning thanks to all the well-paid professionals moving in. Yet I have a hard time looking at all the gleaming new skyscrapers in Tokyo in 2021 and believing that people a few decades from now will be glad we poured public funds and social resources into building ever more houses and offices when the city was on the cusp of population decline, instead of preserving the dwindling cultural heritage that made this place unique and tied together its social fabric.

After dinner at Homeikan, we sat around the ryokan’s large tatami banquet room in our yukata drinking beer and talking. Just before rainy season, the nighttime air was cool and dry enough to keep the window open, and as the clock ticked past midnight, one of my colleagues voiced a point that is hard to escape. Sento served a particular need in the 20th century—supplementing the housing stock of the growing city, or in the case of Fujimi-yu, the last bathhouse within walking distance of Homeikan, serving the geisha who worked in a nearby quarter in Hakusan. Fujimi-yu survived until last October, but its original purpose had long since faded away. The same is true of Hongo’s last ryokan. It is difficult to justify preserving something that in purely economic terms no longer needs to exist.

Urban life has changed. Most travelers today want fancy modern hotels or IKEA-filled boxes on AirBnb. People want to press a button in their kitchen and have the bath fill itself each night while they browse UberEats options on their phone, or visit the sprawling hot-spring spa that sits atop a shopping mall next to Bunkyo City Hall, rather than wander through the streets each night with a basket of shampoo and underwear to wash shoulder to shoulder with their neighbors. That’s the nature of modernization—of human nature, perhaps.

In the face of economic obsolescence, one strategy is to update for modern times. Before covid, many ryokan had shifted heavily towards foreign clientele. Several bathhouses have attracted attention in recent years by re-branding and reorganizing their spaces to appeal to a younger, more social media-savvy crowd. This can be successful when well-executed, though I worry that changing the character of bathhouses too much can leave the elderly and more vulnerable out in the cold, or simply detracts from the charm of sento as a democratic spaces of everyday life that sets them apart from more modern, leisure-oriented facilities.

I want to believe that we can revive Tokyo’s sento by recalling how the city itself, if we disrobe from the frictionless convenience we have grown accustomed to, is not so different from a communal bath—a place where we rub shoulders, encounter difference, and derive satisfaction from occupying a specific place together with others. If bathhouses are no longer an essential part of the urban fabric, it is not a problem with the bathhouse, it is a problem with what have become normal ways of inhabiting the city. If tens of millions dollars of public money can be spent on redevelopment projects and tens of billions on the Olympics, but the last jewel of a local neighborhood’s cultural and architectural heritage must meet the wrecking ball, it is a problem with the way that our society ascribes value to urban space.

The project we are embarking on at Inari-yu is one small way to take a stand against this relentless erasure of Tokyo’s soul, to enact a city we would rather live in, and to say that neighborhoods should belong to the people who live within them and not those who trade their real estate. It may not be enough to stem the decline of the city’s sento or bring back the lost city from the dead, but perhaps it will change a few minds, make people imagine that another form of urban life is possible, and with luck, be the beginning of something larger.

I will write much more about history, architecture, and social meaning of bathhouses in the months ahead. In the meantime, follow us on Facebook and Instagram, and happy bathing.

—

P.S. On the subject of bringing bathhouses back from the dead, several of my Sento & Neighborhood colleagues have built a sento “dashi” (festival float) using items saved from demolished bathhouses, and will be pulling it through the streets this month and next as part of the Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021. I put together a simple site for them, and will be leading a sento-themed walking tour through Kuramae on August 1 as part of related programming, when the dashi will be parked in Akihabara. If any of my gradually growing subscribers are in Tokyo, you’re welcome to join. And if you know anyone who might be interested in my musings on urban development, sento, akiya, capitalism, and the like, feel free to forward this along to them. Thanks!

This is so refreshing to read.

I remember our local bath in Osaka [ 寿楽温泉 ] was closed just after we moved away. It was a necessity for us living in an old machiya with no shower. But, it was also such a deep pleasure that helped me feel like part of the community. I heard after the closure, that it recently re-opened with the help of a local hospital. The value of a sento is so much more than just a bathing place, and I am glad many others seem to see this as well.

Speaking of that, you might enjoy this one:

https://thepossiblecity.substack.com/p/short-28-peace-of-steam-the-japanese

Thanks for sharing your work. Keep it up.

Came across your article when I wanted to learn more about Sento culture and really enjoyed it!

I appreciated the different perspectives you shared—on why these public spaces are invaluable and on the fact that modern day living have strayed away from it.

It makes me wonder—if there’s a way to make a case for these public spaces by addressing exactly that loneliness that people living in big cities like Tokyo (or in my case London) often feel. I often long for that sense of community that I grew up with in Taiwan—the trust in my neighbors and simply enjoying seeing them and saying hi in the day to day. But that closeness or trust is not big cities living—with a lot of people coming and going (sometimes forcibly because rent increase)—lends itself to.

When I went to my first sento two days ago—I immediately felt like this would be exactly the kind of space where people, even and perhaps especially for those who are most trapped in the capitalist system, can feel more connected to their surroundings.

Hope your work goes well and excited to learn more!